GASTROSCHISIS: INCIDENCE AND ASSOCIATED FACTORS

Keywords

Gastroschisis; Risk Factors; Congenital Anomalies; Incidence Abstract

Introduction: Gastroschisis is an abdominal wall defect closure with externalization of intra-abdominal structures, without fully established cause. Its prevalence has increased in various populations, making it a public health issue. The clinical description of new cases and the investigation of associated factors in each population is important for better understanding of disease etiology and adoption of preventive measures.

Objectives: To describe a series of cases of gastroschisis identifying the incidence and associated factors.

Methods: A total of eight cases of newborns (NB) with gastroschisis in a teaching hospital from April 2011 to April 2012. The variables analyzed were collected from the study database “Characterization and Clinical Epidemiology of Congenital Anomalies in the Maternity of two Hospitals School of Vitória – ES “and the medical records of mothers and newborns. The patients born during this period were investigated for the presence of congenital anomalies.

Results: There were eight cases of gastroschisis described, which was compared with 1139 RN without congenital anomaly. None of the cases mothers had higher education level five planned pregnancy, 87.5% of primiparous mothers, with a median maternal age of the cases (21 years old) reduced compared to the control group (26 years old) p = 0.0089). 12.5% was observed familial recurrence. Death occurred in three cases, one with karyotype 46, XX inv.9.

Conclusion: Mortality rates, prematurity and low birth weight were very high. The occurrence of gastroschisis was associated with low maternal age, socioeconomic and genetic factors.

Introduction

Gastroschisis is a congenital malformation (OMIM 230750) characterized by a defect in the abdominal wall, with the externalization of abdominal viscera, especially the intestine. Usually there are no alterations in the umbilical cord due to the fact that the defect is located at the junction of the umbilicus and normal skin and usually to the right.1

The most accepted hypothesis to explain the etiology of the defect is the occurrence of ischemia of the abdominal wall during its development. Between the 5th and 8th weeks of embryogenesis a nutritional transition occurs, with the involution of the right umbilical vein to the right omphalomesenteric artery. Embryo disruption of these vessels or the mismatch in the timing of this transition may cause vascular ischemia.2 Although well accepted, this hypothesis does not explain the cases of gastroschisis to the left. Another hypothesis related to the etiology of gastroschisis is the hypothesis of the three parts. This consists of (1) an early estrogenic thrombophilia, which occurs mainly in the first trimester of pregnancy in young primigravida mothers; (2) different responses to thrombosis, according to ethnicity and (3) thrombotic byproducts which can interfere with early developmental signaling.3 Besides these, Jones et al (2013) recently suggested the hypothesis that a maternal inflammation during early pregnancy, possibly resulted of imbalance in fatty acid metabolism, can lead to vascular disruption.

The prevalence of gastroschisis is progressively increasing in all regions of the world. Next to the 60s when the monitoring programs and data collection on congenital malformations started, it was 1: 50,000 births and has increased about 10 to 20 times in various populations ever since. Currently, it presents reasons of 1-2 to 4-5 per 10,000 depending on the studied population. According to data of Latin American Collaborative Studio of Congenital Malformations (ECLAMC), the prevalence in South America is 2.9: 10,000.4

Etiologies of gastroschisis are largely unknown, and even its pathogenesis is poorly understood. The non-genetic risk factors for gastroschisis includes sociodemographic, being education level the most important, maternal therapeutic medication, exposure to non-therapeutic drugs, being reduced maternal age (< 20 years old), smoking, illicit drug addiction the most replicated factors.5 On the other hand, there is no consensus on the contribution of genetic factors, being observed familial recurrence in 4.7% of cases. Recent studies have identified interaction between maternal smoking, genetic variants (single nucleotide polymorphism - SNP) in the enzyme gene nitric oxide synthase and the risk of gastroschisis.5

The objective of this study is to report the incidence of gastroschisis, with the description of eight cases and associated factors.

Method

This retrospective study is part of the project “Clinical and Epidemiological Characterization of Congenital Anomalies in the Maternity of two Teaching Hospitals of the Municipality of Vitória – ES” (approved in CEP EMESCAM under no. 148/2010), a cross-sectional study involving four higher education institutions, maternity units of two teaching hospitals and a children’s hospital of reference in the state of Espírito Santo (ES), which was aimed at the clinical and epidemiological characterization of the CA in the ES, through the clinical evaluation of the newborn (NB) in maternity wards of teaching hospitals Hospital Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Vitoria (HSCMV) and Hospital Cassiano Antonio de Moraes of the Federal University of Espírito Santo (HUCAM / UFES). The participation of the NB and his mother in the research was authorized by signing the Terms of Consent. Data from mothers who participated in the research were obtained through interviews and analysis of the records. For twelve months, the NB were evaluated 24 hours after birth by neonatologists and pediatricians for the presence of major and minor CA using, during the physical examination, the modified protocol of Merks et al (2003). Among the evaluated NB, those with at least one major anomaly and those with at least 3 or more minor anomalies were referred to genetic clinics at Hospital Infantil Nossa Senhora da Glória (HINSG), for specific clinical evaluation, monitoring of patients and families, diagnosis and genetic counseling. Peripheral blood was collected for cytogenetic and/or DNA study, which was isolated using commercial kits (Gentra and Puregene Blood Kit, Qiagen). Clinical data, karyotype, and additional tests were analyzed by staff and used to establish the etiology of the CA with regard to the type and frequency of genetic alterations. Clinical data of these mothers and their NB were placed in a database containing about 70 variables.

Variables of mothers, fathers and NB diagnosed with gastroschisis in HUCAM were obtained from the database and medical records of mothers and NB. Families were approached in hospitals, address and through phone. The following variables of NB were analyzed: sex, gestational age (GA), anthropometric parameters (weight, length, head circumference and appropriate weight for gestational age), prematurity, associated CA (major and minor), family history of CA and karyotype (when available), hospitalization time and outcome. In addition to these, were investigated age and occupation of both mother and father, maternal education, parity, abortion, stillbirth, pregnancy planning, use of folic acid, presence of chronic diseases, TORCH’s agents serology (when available), exposure to drugs, alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs. Every NB with GA less than 37 weeks was considered premature6, and birth weight was considered low when less than 2500g and very low when less than 1500g.7

Patients who have been diagnosed with gastroschisis were considered cases and patients without AC were considered controls.

Statistical analysis was performed using the program GraphPad Prism and SPSS version 11.0. The Kolmogorow-Smirnov test was used to verify if the variables presented normal distribution. Variables where the probability distribution was not normal, the average was considered and the Mann Whitney test applied. Categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Χ2 values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

From April 2011 to May 2012 were attended 1242 NB in Hospital Santa Casa and 1057 in HUCAM totaling 2299 NB, being 1148 (49.94%) female and 1,145 (49.8%) male. Undefined sex was observed in three cases (0.13%): two with ambiguous genitalia and one without external genitals and anus. In other three it was not possible to obtain this information. Of 2299 NB studied eight were diagnosed with gastroschisis (cases), resulting in an incidence of approximately 1/287 births. All newborns with gastroschisis were born in HUCAM, hospital that attends high-risk pregnant women.

The control sample consisted of 1139 NB (49,54%), being 575 (50,48%) female and 564 (49,52%) male.

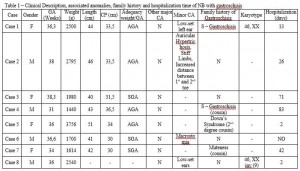

Of the eight cases, there were four males and four females. The median GA was 36 weeks (31-38 weeks) and six births were preterm. The median birth weight was 2.240g (1440g – 3756g), four infants with low birth weight, one of them being classified as very low. In the occurrence of associated abnormalities, it was found the presence of more than one CA in three cases. Of the three NB that died, two had associated CA. In three cases the family history of CA was positive, and in one of them, there are reports of gastroschisis in a cousin (Table 1).

Maternal age ranged from 13 to 25 years old, being the median 21 years old (13-26; IC95%: 17.16-23.84). In the control sample (N = 1133), the median was 26 years old (14-64, 95% CI 26.43 to 27.22; P = 0.0089). Two mothers had less than twenty years old, three twenty years old and three above this age. Seven mothers were primigravida, and only one multigravida (G3). No cases of stillbirth or miscarriage was found in the analyzed sample. Five mothers planned pregnancy, in two the pregnancy was unplanned and in one case this information was not possible. All mothers had used folic acid only during pregnancy. It was observed that one mother had Familial Hypercholesterolemia and other Hypertensive Disease of Pregnancy. Serology for syphilis, hepatitis B and HIV were negative in three mothers, and in two of them found seronegative also for hepatitis C, toxoplasmosis and rubella. Two mothers denied the use of both alcohol as tobacco and illicit drug use during pregnancy and was not found data on these variables in the records. Analyzing the socioeconomic factors there is the education level, in which three had complete primary education, and five had finished high school, training at a higher level was not observed. Paternal age ranged from 18 to 26 years old (median 22.5 years old).

Discussion

The incidence of gastroschisis in the studied hospital was of 1: 287 births, which concurs with the data from different regions of Brazil and the world, which show an increase in this incidence. In the 60s, after the implementation of monitoring programs and data collection related to congenital malformations in many countries, the incidence was estimated at 1: 50,000 births. In the last two decades it was observed an increase in this rate, according to data from the Latin American Collaborative Study of Congenital Malformations (ECLAMC), the prevalence in South America is of 2.9: 10,000.4 Should be highlighted that the eight NB were born in the maternity ward of a hospital that serves high-risk pregnancies.

Hunter and Stevenson8 reported that there is a relation of prematurity and low birth weight with gastroschisis, this fact observed in our study, in which prematurity was seen in six NB with median GA of 36 weeks and weight of 2.240g, being the low birth weight in four of them and considered appropriate in only four cases. According to these authors, in the big series published in the last two decades, the average gestational age was 36.2 weeks and the average weight was 2400g.

The presence of severe CA, or genetic syndromes associated with gastroschisis is infrequent, occurring in 6.8% to 20% of cases, but there may be local malformations such as atresia or intestinal stenosis.9 However, Patroni et al10, analyzing 24 cases, found a high incidence, around 37.5%. The incidence found in this study was 50%, higher than those reported so far (Table 1), possibly by using the modified protocol Merks et al (2003), neonatologists and pediatricians team training, as well as triage held in the maternity.

It should be highlighted that the use of this protocol contributes to the identification of several minor CA, observed in four cases, being the ear abnormalities the most common. In both cases the karyotype was performed, one shown normal result and the other found a variant of normality (Table 1).

Poulain et al11 also found high association rates with other CA (20% or more), such as congenital clubfoot, micrognathia, clinodactyly, holoprosencephaly, unilateral absence of the ulna and radius, and aneuploidy, concluding that although gastroschisis is less often associated with other malformations and congenital anomalies, it is prudent to carry out a detailed ultrasound and karyotype analysis in all cases.

An interesting data was observed in relation to chromosomal alterations considered “normal variants”, which are found in 3-4% of the general population, being more common in black individuals (3.57%) than in white people (0.73%), in women and in patients with Down Syndrome. In this work one NB presented the variant inv9 and died. There is controversy as to the pathogenicity of these variants, however, some authors show positive association with reduced fertility, leukemia, schizophrenia, abortions and unspecific CA12. With use of the genomic methodologies this controversy can be clarified.

The main variables related to deaths in NB with gastroschisis are low birth weight, prematurity and presence of infections13, but none of these are specific factors of this CA. The complexity of gastroschisis is a specific factor for the increasing of morbidity and mortality. Such complexity is determined by large intestinal impairment, sepsis or complications of Short Bowel Syndrome9. In our study we observed that in one case the cause of death was pneumonia, possibly due to long periods of mechanical ventilation14. In another case observed as a cause of death, hypovolemic shock and renal failure; This patient required reoperation, and had severe edema handle, prognosis complicating factor.

Some studies discuss the influence of prenatal care on mortality rate for patients with gastroschisis. A retrospective study showed an association between non performing prenatal care and a higher mortality rate of patients with gastroschisis. According to these authors, when prenatal care is not performed properly, the diagnosis of gastroschisis is not made during this period and thus, there is no proper management of patients15. Also in this study, Sbragia et al15 found that lacking the knowledge of having of this CA during pregnancy probably results in absence of additional care during childbirth, which aim to reduce the contamination of the abdominal cavity. In addition, they observed that prior knowledge of gastroschisis enables maternal transfer to a tertiary care center, providing most appropriate decision making regarding the child. In this study, only one of the mothers did not follow the prenatal and their NB did not come to death. In a national study, Vilela et al16 reported a mortality of 53% of cases of gastroschisis in a northeastern population of Brazil.

However, they studied a population where access to good care is precarious. In this series of cases a mortality rate of 37.5% was observed and even though high is still lower than in some Brazilian regions, such as Northeast that comes to be 52%.4 Unlikely, developed countries have low mortality, and survival is above 90% in these locations. The mortality rate of 25% (2/8) is smaller than those found in the Northeast and in Porto Alegre.

With regard to maternal age, a median of 20 years old (13-25 years old) was obtained, which corroborates data from other studies, such as Feldkamp et al5, in which the low maternal age (< 20 years old) is shown as a risk factor for the onset of gastroschisis. Regarding socioeconomic factors, it was seen that none of the mothers had higher education, and that five of them had completed high school. Vu et al17, found that in California the prevalence of gastroschisis was higher in mothers with lower education levels, i.e., who did not have completed high school (46.27%). In a study conducted in Brazil between 2000 and 2004, Guerra et al18 observed a higher frequency of CA, including gastroschisis, in NB of mothers with fewer years of schooling; Furthermore, they found that The difference of prevalence among women with lower education levels and those with 12 years or more of schooling increased throughout the study period, reaching a maximum in 2004: 106.5/10,000 (0-7 years of schooling) and 60.8/10,000 (12 and more years of schooling). More recently, in case-control studies, Nhoncanse et al19 found a greater number of mothers with education level of eight or less years of schooling in the group with CA (cases). These authors reported that there is probable evidence that low education level is responsible for the increased exposure to teratogens, due to the poor level of knowledge of the risks involved. However, the latter two studies have analyzed the relationship between education and gastroschisis directly, only evaluated the level of education regarding birth defects, even if gastroschisis was included among them. However, contrary results were obtained by Reis and Ferrari20, which sought to identify the sociodemographic profile of mothers of NB with CA, and found a higher number of cases of CA in NB of mothers with secondary education (37.9%) when compared to mothers with primary education (5.2%) or no education (0.6%) in a total of 174 cases. The use of illicit drugs has shown strong risk factor for the onset of gastroschisis, especially when using more than one drug in combination (cocaine, amphetamines and marijuana) or if compared to single use in which both parents make use of narcotics. This is shown by the study of population-based data from the California Birth Defects Monitoring Program - USA (CBDMP), directed by Torfs et al21. The increased risk by smoking is higher in older women (> 25 years old) and in higher socio-economic groups.22,21 None of pregnant women in this study reported use of alcohol, tobacco or illegal drugs.

Some patients make use of medications such as methyldopa, Bromopride, Clonazepam and Etilefrine Hydrochloride, however, there are currently no studies that prove the relationship of these medications with the onset of the disease. In one study, Aceves et al23 demonstrated a relationship between the onset of gastroschisis and the use of hormonal contraceptives during first trimester of pregnancy. In another study, by Mac T. Bird et al24, the use of ibuprofen was revealed as a risk factor, however, in our study did not report the use of these medications for any of the mothers. Torfs et al25 also mentioned the use of ibuprofen, aspirin and decongestants as strong risk factors and on the other hand has shown that antibiotics, antiemetics, sulfonamides and oral contraceptives do not offer risk.

Conclusion

Mortality rates, prematurity and low birth weight associated with gastroschisis were very high. The incidence of gastroschisis was associated with low maternal age, the presence of other minor congenital anomalies and socio-economic and genetic factors. The incidence of gastroschisis observed in this study was very high and the observed associations suggest the need for further investigation, proposal and adoption of preventive measures.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient’s family for the cooperation. We are grateful to the research team and undergraduate students of the Congenital Anomalies Project. We are also grateful to the Hospital Universitário Cassiano Antônio de Moraes (HUCAM), Hospital Santa Casa, Hospital Infantil Nossa Senhora da Glória (HINSG). To the Escola Superior de Ciências da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Vitória (EMESCAM), to Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Espírito Santo (FAPES) and National Council for the Development of Science and Technology (CNPq) for Scientific Research Initiation Scolarships to RMT (FAPES), LRSS (EMESCAM), VOB (EMESCAM), IHAB (CNPq), RCMQ (FAPES), MDP (FAPES), PGR (FAPES), AXF (FAPES). This research was supported by the Ministry of Health Department of Science and Technology (DECIT) – Research Program for the Unified Health System (PPSUS/50809717/2010), Espírito Santo State Secretary of Health (SESA), Espírito Santo Research Foundation (FAPES), CNPq also through Casadinho/PROCAD 06/2011 (Nº552672/2011-4), and São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP/CEPID).

References

1. Castilla EE, Mastroiacovo P, Orioli IM. Gastroschisis: international epidemiology and public health perspectives. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2008 Aug 15;148C(3):162-79.

2. Hoyme HE, Higginbottom MC, Jones KL. The vascular pathogenesis of gastroschisis: intrauterine interruption of the omphalomesenteric artery. J Pediatr. 1981 Feb;98(2):228-31.

3. Lubinsky M. Hypothesis: Estrogen related thrombosis explains the pathogenesis and epidemiology of gastroschisis. Am J Med Genet A. 2012 Apr;158A(4):808-11. Epub 2012 Mar 1.

4. Calcagnotto H, Müller ALL, Leite JCL, Sanseverino MTV, Gomes KW, Magalhães JAA. Fatores Associados à Mortalidade em Recém-Nascidos com Gastrosquise. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. [online]. 2013; 35 (12): 549-553.

5. Feldkamp ML, Botto LD. Developing a research and public health agenda for gastroschisis: how do we bridge the gap between what is known and what is not? Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2008 Aug 15;148C(3):155-61.

6. Catherine Y, Spong MD. Defining “Term” Pregnancy – Recommendations From the Defining “Term” Pregnancy Workgroup. JAMA Network. 2013; 309 (23): 2445-2446.

7. Minamisava R, Barbosa MA, Malagoni L, Andraus LMS. Fatores Associados ao Baixo Peso ao Nascer no Estado de Goiás. Revista Eletrônica de Enfermagem. 2006; 06 (03).Disponível em:

8. Hunter AG, Stevenson RE. Gastroschisis: clinical presentation and associations. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2008 Aug 15;148C(3):219-30.

9. Calcagnotto H. Gastrosquise: Diagnóstico Pré-Natal, seguimento e Análise de Fatores Prognósticos para Óbito em Recém-Nascidos [Dissertação de Mestrado em Ciências Médicas]. Rio Grande do Sul: Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, 2010. 87f.

10. Patroni L, Brizot ML, Mustafá AS, Carvalho MHB, Silva MM, Miyadahira S, et al. Gastrosquise: Avaliação Pré-Natal dos Fatores Prognósticos para Sobrevida Pós-Natal. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. [online]. 2000; 22 (7): 421-428.

11. Poulain P, Milon J, Frémont B, Proudhon JF, Odent S, Babut JM, et al. Remarks about the prognosis in case of antenatal diagnosis of gastroschisis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994 May 18;54(3):185-90.

12. Jeong SY, Kim BY, Yu JE. De novo pericentric inversion of chromosome 9 in congenital anomaly. Yonsei Med J. 2010 Sep;51(5):775-80. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2010. 51.5.775. PubMed PMID: 20635455; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2908878.

13. Amorim MMR, Vilela PC, Santos LC, Falbo GH Neto, Lippo LAM, Marques M. Gastrosquise: Diagnostico Pré-natal x Prognóstico Neonatal. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet.[online]. 2000; 22 (4): 191-199.

14. Carvalho CRR.Pneumonia Associada à Ventilação Mecânica. J. bras. pneumol. [online]. 2006; 32 (4): xx-xxii.

15. Sbragia L Neto, Melo AA Filho, Barini R, Huguet PR, Marba S, Bustorff-Silva JM. Importância do Diagnóstico Pré-Natal de Gastrosquise. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 1999; 21 (8): 475-479.

16. Vilela PC, Amorim MMR, Falbo GH Neto, Santos LC, Santos RVH, Correia C. Fatores Prognósticos para Óbito em Recém-Nascidos com Gastrosquise. Acta Cir. Bras. [online]. 2002; 17 Suppl.1: 17-20.

17. Vu LT, Nobuhara KK, Laurent C, Shaw GM. Increasing prevalence of gastroschisis: population-based study in California. J Pediatr. 2008 Jun;152(6):807-11. Epub 2008 Feb 1.

18. Guerra FAR, Llerena JC Jr.,Gama SGN, Cunha CB, Theme MM Filha. Defeitos Congênitos no Município do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil: uma avaliação através do SINASC(2000-2004). Cad. Saúde Pública [online]. 2008; 24 (1): 140-149.

19. Nhoncanse GC, Germano CMR, de Avó LRS, Melo DG. Aspectos Maternos e Perinatais dos Defeitos Congênitos: um estudo caso-controle. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2014; 32 (1): 24-31.

20. Reis LLAS dos, Ferrari R. Malformações Congênitas: Perfil Sociodemográfico das Mães e Condições de Gestação. Rev enfer UFPE online. 2014; 4 (1): 98-106.

21. Torfs CP, Velie EM, Oechsli FW, Bateson TF, Curry CJ. A population-based study of gastroschisis: demographic, pregnancy, and lifestyle risk factors. Teratology. 1994 Jul;50(1):44-53.

22. Paranjothy S, Broughton H, Evans A, Huddart S, Drayton M, Jefferson R, et al. The role of maternal nutrition in the aetiology of gastroschisis: an incident case-control study. Int J Epidemiol. 2012 Aug;41(4):1141-52.

23. Robledo-Aceves M, Bobadilla-Morales L, Mellín-Sánchez EL, Corona-Rivera A,Pérez-Molina JJ, Cárdenas-Ruiz Velasco JJ, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for gastroschisis in a public hospital from west México. Congenit Anom(Kyoto). 2014 Sep 22. [Epub ahead of print]

24. Mac Bird T, Robbins JM, Druschel C, Cleves MA, Yang S, Hobbs CA. National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Demographic and environmental risk factors for gastroschisis and omphalocele in the National Birth Defects Prevention Study. J Pediatr Surg. 2009 Aug;44(8):1546-51.

25. Torfs CP, Katz EA, Bateson TF, Lam PK, Curry CJ. Maternal medications and environmental exposures as risk factors for gastroschisis. Teratology. 1996 Aug;54(2):84-92.

Attachments

Legend: F: Female; M: Male; GA: Gestational Age; CP: Cephalic Perimeter; AGA: Appropriate for Gestational Age; PIG: Small for Gestational Age; Y: Yes; N: No; CA: Congenital Anomaly. Source: author. Note: translated.

Authors

Rafaela Martins Togneri¹; Hector Yuri Conti Wanderley2; Andrea Lübe Antunes de S.Thiago Pereira3; Luiz Roberto da Silva Santos4; Vitor Ohnesorg Barbieri5; Maria do Carmo de Souza Rodrigues6; Larissa Souza Mario Bueno 7; Vera Lucia Maia 8; Geisa Hossokawa Eguchi Neves9; Sandra Willéia Martins 10; Ingrid Hellen André Barreto11; Renata Cristina Moreira Queiroz12; Marya Duarte Pagotti13; Aline Ximenes Fragoso14; Polyana Gonçalves Rocha15; José Carlos Frasson16; Regina Galvêas Oliveira Rebouças17; Maria Rita Passos Bueno18; Eliete Rabbi Bortolini19; Flávia Imbroisi Valle Errera20*

1,4,5,11,12,13 Scholarship Holder of Undergraduate Research Internship – (Medical School Undergraduate – EMESCAM).

2 Specialist in Medical Genetics – UFRGS – (State Coordinating Doctor, Hospital Infantil Nossa Senhora da Glória).

3 Master’s Degree in Pediatrics and Pediatrics Applied Sciences, UNIFESP – (EMESCAM Neonatology professor. Pediatrician and Neonatologist of Hospital Santa Casa and Hospital Universitário Cassiano Antônio de Moraes – HUCAM, UFES).

6 Master’s Degree from the School of Medical Sciences, UERJ – Doctor Geneticist at HUCAM/UFES. Specialist in Medical Genetics – Brazilian Society of Medical Genetics/Brazilian Medical Association.

7 Master’s Degree in Medical Sciences, UFRGS – Doctor Geneticist at Hospital Estadual Infantil Nossa Senhora da Glória, Vitória, ES, Brazil.

8 PhD in Physiological Sciences, UFES – (Pediatrician at HUCAM – UFES).

9 Resident Doctor in Neonatology/Hospital Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Vitória – HSCMV.

10 Master’s Degree and PhD in Psychology – UFES – Neonatologist – HUCAM/UFES.

14 Educational Association of Vitória’s Scholarship of Scientific Initiation – (Master’s Degree Student in Public Policy and Local Development).

15 Pharmacist – Scholarship of Technical Support/ EMESCAM.

16 Surgeon – Hospital Universitário Cassiano Antônio de Moraes/UFES.

17 Master’s Degree in Genetics – USP – (Doctor Geneticist at Hospital Infantil Nossa Senhora da Glória and Universidade Vila Velha – UVV-ES).

18 PhD in Genetics – USP – Biologist, Senior Genetics Professor, Human Development Genetics Laboratory, Department of Genetics and Evolutionary Biology, IB, USP.

19 PhD in Genetics – USP – Biologist, Educational Association of Vitória.

20 PhD in Genetics – USP – Biologist, Professor of Genetics and Molecular Biology and Coordinator of Molecular Genetics Laboratory at EMESCAM.