ELABORATION OF PRESSURE ULCER PREVENTION PROTOCOL

Abstract

Introduction: Pressure ulcers are a major health problem causing complications to the patient and increased hospital costs due to its high cost of treatment. However, it is an entirely preventable disease avoiding its severe consequences. Objective: A pressure ulcer prevention protocol was developed, in order to systematize assistance to patients in risk of their development, and also to establish preventive measures with the resources available at Hospital Santa Casa de Misericordia de Vitoria (HSCMV), through multidisciplinary approach to family / caregivers. Method: This is a study with a non-experimental research design, descriptive, literature review type. Conclusion: It has been concluded that it is advantageous to implement this protocol, reducing thus the variability of clinical management, ensuring a more qualified patient care.

Introduction

Popularly known as scabs, the pressure ulcer (PU) is a skin lesion and/or a lesion on the underlying tissue caused by isolated pressure or pressure combined with friction and / or shearing (pressure exerted when the patient is moved on a bed or a chair) between the skin and an external surface. It usually occurs in bone protuberance regions in contact with a support surface. This prolonged compression generates a local blood flow reduction, reducing nutritional offer and tissue oxygenation, favoring tissue ischemia and necrosis ocurrence1.

It is a common condition but largely avoidable, that has an important economic impact on the health system. The costs related to PU care are the third largest expenditures after cancer and cardiovascular diseases.2,3 This is due to hospitalization time lengthening especially, and also the patient condition deterioration, increasing the risks for infections like osteomyelitis and sepsis. 1,2

he interest to develop this work has been raised, when high rates of PU were verified along medicine internship practices in several wards at Hospital Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Vitória. Information and the most relevant data related to pressure ulcer prevention were put together in a protocol format to be used since patient admission to patient leave, reducing clinical

management variability and ensuring the patient a more qualified care. A handout folder has been designed with important guidance for vulnerable patients caregivers, allowing them to identify early lesions and start its prevention.

Epidemiology

UP incidence rates vary largely in the literature, due to the care level characteristics, differing in severe care, long stay care and home care. In the USA, PU incidence ranges from 0.4% to 38% in severe care; from 2.2% to 23.9% in the long stay care, and from 0 to 17% in home care.2

There are a few studies about PU incidence in Brazil. However, they have demonstrated that the estimated clinical medicine PU incidence is 42.6%; in surgery units, 39.55; and in intensive care units ranges from 10.62% to 62.5%. This large incidence suggests insufficient deliveries from the health care professionals to the hospitalized patients.4

Individual susceptibility depends upon a series of factors conjugated with tissue perfusion alterations. Intrinsic risk factors (inherent to the individual) for PU include old age, bedding restrictions, tobaccoism, cognitive and sensorial disabilities, malnutrition and other comorbidities affecting tissue integrity and cicatrization (as urinary incontinence, edema, hypoalbuminemia, malnutrition and conditions affecting blood microcirculation). Extrinsic risk factors related to the lesion mechanism and related to the lesion mechanism and related to the lesion mechanism and independent of the individuals) include forces like friction and shearing, humidity and positioning. Patients for long periods in bed are the main group of lesion development. These risk factors must be always assessed by the health professionals during patient admissions.1,3

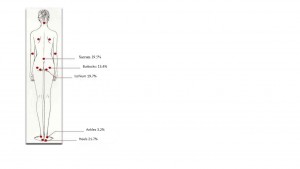

There are no body surfaces immune to the ischemic effects of haste, but PU frequently occurs over a bone prominence. The PU most affected regions are the heel bone (21.7%), the ischium (19.7%), the sacrum (19.5%), the buttocks (13.4%) and the ankles (3.4%), as shown on Figure 1.

Figure 1: Most affected PU regions

Source: Figure modified by the authors. Obtained at: https://br.pinterest.com/pin/313844667756781823/

Furthermore, ulcers in the extremities is a factor associated to cicatrization time. Thus, the heel bone PU, being the most common one and a longer cicatrization time concern, must be targeted with specific preventive measures.3,5

Classification

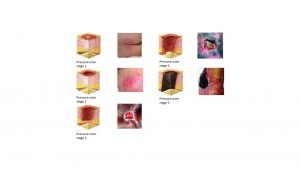

Pressure ulcers are wounds classified by severity and depth. The staging system most commonly used is the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP). This classification is described in Figure 2.

Figure 2: PU classification

Source: Figure modified by the authors. Obtained at: http://www.npuap.org/resources/educational-and-clinical-resources/pressure-ulcer-categorystaging-illustrations/

Risk and management stratification

PU risk scale adoption aids decision taking, helping the health provider to figure out the care plan and program the preventive medical conducts. Braden scale (Figure 3) is the most largely adopted, gathering the following factors: sensorial perception, humidity, activity, mobility, nutrition, friction and shearing. Its usage during risk factors assessment allows the patient clinical condition verification.1

Figure 3: Braden Scale

| Patient name:_______________________ Gender:___ Age: ____ | |||

| Inspector name:______________________ Date: ___/___/_____ | |||

| Aspects | Assessment | Score | |

| Sensorial Perception | Totally limited

Sensorial Very limited Slightly limited No limitation |

1

2 3 4 |

|

| Moisture | Totally wet

Very wet Occasionally wet Rarely wet |

1

2 3 4 |

|

| Activity | Bedridden

Chair restrained Walks occasionally Walks frequently |

1

2 3 4 |

|

| Mobility | Totally motionless

Strongly limited Slightly limited No limitations |

1

2 3 4 |

|

| Nutrition | Very poor

Probably inadequate Adequate Excellent |

1

2 3 4 |

|

| Friction & Shearing | Problem

Potential problem No problem |

1

2 3 |

|

| TOTAL | |||

Source: figure modified by the authors. Obtained at the journal: Which factors predict incident pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients? A prospective cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2014 Jun;170(6):1285-90.

The nursing professional is one of the main caregivers of bedridden patients with pressure ulcers, however, prevention of UP is a multidisciplinary process that begins in the recognition of patients at risk and prompt institution of specific preventive measures for these patients, once the common sense among authors say that preventing UP is less costly and more important than the proposed treatment.6

Objectives

General objectives

Elaborate a prevention protocol for pressure ulcer, to be established in the wards of the Santa Casa de Misericordia de Vitoria Hospital.

Specific objectives

Systemize risk patient assistance and establish preventive measures accordingly with the availability of resources at Santa Casa de Misericordia de Vitoria Hospital (HSCMV), with a multidisciplinary approach to the patient’s family members and caregivers.

Justification

Pressure ulcer prevention is relevant not only for the patient, reducing morbidity and hospital time, but for the hospital too, reducing costs. Looking at the collected data and also looking at the few practical protocols in use, it does characterize this instrument development action as a valid and necessary step.4

Method

Study design

This is a study with a non-experimental outline, a descriptive and qualitative literature review type. PubMed site databases MEDLINE, SciELO and LILACS-BIRREME national and international literature were reviewed, and a selection of papers published in the last 15 years addressing pressure ulcer has been done. For each above-mentioned database, the following key words have been used: 1) pressure ulcer, 2) protocol, 3) pressure ulcer prevention, as the primary descriptors. The secondary descriptors have been: 1) pressure ulcer protocol, 2) pressure ulcer treatment. Bibliography research has included original prospective and retrospective research papers, review papers, editorials and directives written in the Portuguese, Spanish and English idioms, listed by their relevance. A 15 Year Bibliography Review, PubMed classified pursuant to their relevance has been researched, and 19 papers were selected subjectively, taking into account their epidemiological importance, prevention measures and clinical management.

Assessment tool elaboration

The tool has been developed upon the prevention sections from the recommendations and guides of NPUAP (National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel) 2014, EPUAP (European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel) and PPPIA (Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance), where preventive recommendations are also described and supported by evidence based medicine. In the same way, the 2013 Ministry of Health Protocol has been complementarily used, with its relevant information and recommendations. Braden Scale has also been used to stratify PU risks.

Pressure ulcer prevention educational hand-out making

The PU Educational Handout was developed upon the prevention sections from the recommendations and guides of NPUAP (National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel), EPUAP (European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel) and PPPIA (Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance), where preventive recommendations are also described and supported by evidence based medicine. In the same way, the 2013 Ministry of Health Protocol has been complementarily used, with its relevant information and recommendations.

Pressure ulcer protocol

An early and personal intervention program developed for each patient is essential for a care plan. This protocol is a six step strategy, fundamental each one of them, for an effective PU prevention. It has been divided into PU development risk assessment that must be done by the health professional with each patient at hospital admission, to spot high-risk individuals. Daily skin inspection, constantly looking for skin changes; with hygiene maintenance and care. Nutritional support and pressure relief, with special concern with decubitus changes and early deambulations, when possible; and educational hand-out delivery and explanations to the family members and/or caregivers. 7-10

Interaction among health professionals, patients and family members/care takers is necessary, stressing the importance of discipline, participation and collaboration along hospital stays.

First step: PU risk assessment at admission

It is done in an objective and subjective manner, in every patient, independently of his age group. Patients must be systematically checked in the admission moment trough PU development risk assessment, and the skin must be inspected to detect PU already settled.11,12

Risk objective assessment

To asses PU development risk in the hospital admission moment objectively, the nurse shall apply the predictive risk scale, validated in all the patients under internment. Braden predictive scale (Figure 3) has been adopted in this protocol. It is the most widely used one and it shall guide and shape the preventive measures for each patient, pursuant to his / her punctuation. The scale comprises the following assessment subsets: sensorial perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, friction and shearing. Skin inspection must be done on bone prominence regions, mainly on the most common PU settlement sites.1,3

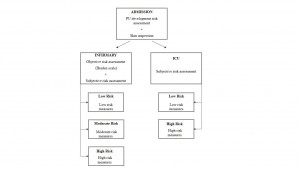

Risk subjective assessment

Braden scale must be always applied together with the nurse clinical judgement. However, Intensive Care Centers patients displayed a poor Braden scale performance. Thus, patients admitted in such centers must be assessed concerning PU development risk only through the nurse subjective assessment, as depicted in the flowchart3 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Risk assessment chart

Source: the author

Second step: Skin daily inspection

The cutaneous surface daily inspection in moderate to high PU development risk (≤ 14 points in the Braden scale) patients must be done from head to toes, checking temperature, the presence of erythemas and blisters, indicators of tissue rupture. Low risk PU patients (15 to 18 points in the Braden scale) inspections must be done every 72 hours. It is worth mentioning that a great attention must be given to the high risk PU corporal areas, like heel, ischium, sacrum, buttocks, ankles, trochanter, malleolus, scapula and occipital.3,11,12

PU classification knowledge is key to allow the detection of early stages lesions, when there is only a non-whitening hyperemia on bone prominence sites. PU diagnostics in early stages enhances an efficient approach to avoid lesion progression.7

Patient decubitus must be changed and the hyperemia site must be assessed again in 15 to 30 minutes when hypermeias are detected. If it does remain, a stage 1 PU is developing. Thus, the patient and the family must be oriented and become aware of the problem. Dialogue with the family is important to clear doubts and shows the health team compromise with the service quality.6

Skin changes found on patient inspection must be entered in the Patient Nursing Datasheet (Figure 5). This document contains the patient name, ulcers location, the most severe ulcer classification regarding its stage (NPUAP), its origin regarding ethiology (community or hospital) and decubitus change schedule. The document must be filled daily and filed with the patient medical records, becoming as such, a key tool to follow his evolution.

| Figure 5: Patient Nursing Datasheet | ||

| Patient name: | ||

| Severe ulcer classification

(NPUAP) |

( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) |

Stage I

Stage II Stage III Stage IV Unclassified Deep tissues lesion suspicion |

| Ulcer localization | ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) |

Heels

Ischium Sacrum Ankles Trochanter Malleolus Scapula Occipital Others: ________________________ |

| Risk assessment (Braden Scale) | ( )

( ) ( ) |

Low risk

Moderate risk High risk |

| Origin | ( )

( ) |

Community

SCMVH |

| Nurse Signature

_____________________________________________________ |

||

| Source: figure modified by the authors. Obtained at the journal: Úlceras de pressão. Rev Bras Geriatr & Gerontol, 2010;4(1):36-43. | ||

Third step: skin hygiene and care

The skin is our largest organ, the first organism defense barrier. Factors like paralysis, numbness and old age lead to skin atrophy, thinning the protective

barrier. It must receive specific care to avoid compromising, once PU is just about breaking this barrier, as a general rule it must be kept clean, well hydrated and without excessive moisture.6 The main recommendations follow below:

. Warm water and neutral soap for bathing to reduce skin irritation and dryness. Avoid hot water and excessive skin friction.6,12

. Moisturizers after bathing (essential fatty acids), hydration at least once a day for old and/or dry skin patients. Dry skin is a PU development risk factor.6

- Do not massage the bone prominence places, nor the hyperemia sites along hydration. Hydratant must be applied smoothly, with soft moves.6,12

- Nursing team must pay attention to urinary and fecal incontinence, as well as to other moisture sources, as sweat and wounds exudate.6

Fourth step: nutritional support

There is a strict relationship between malnutrition and PU development. Pressure ulcer bearing patients or in PU development risk, must have their nutritional stage assessment trough anthropometric measures, done in the moment of the patient admission in the health institution. Those bearing ulcers or under malnutrition risks must be sent to the nutritionist, or to a multidisciplinary team in order to have a full nutritional assessment.2,11

The team will then shape a care plan for these individuals, to correct fortuitous nutritional deficits, as this deficiency increases vulnerability to the trauma, as well as it slows down wounds cicatrization. Energetic individualized nourishment based on medical conditions and on the subjacent activity level. If the calories or proteins ingestion is inadequate, the factors compromising such must be treated as a part of the patient integral assistance.2,11

Fifth step: pressure relief

One of the most important pillars for PU prevention is change the patient decubitus every 2 hours. The patients in bed must be intercalary placed in the four decubitus: ventral, dorsal and laterals in a sequence. Repositioning allows pressure distribution, reducing its scale over the vulnerable body areas, keeping the blood flowing in the major PU development risk areas.2,11,12

It is fundamental that the patient and his/her caregiver are aware of the preventive measures importance. Family awareness is key to unite efforts together with the medical and the nursing teams, once informed individuals have less PU development risks and less acuteness along patient condition evolution. These are the reasons why it is essential to develop and apply educational measures with those involved with the patient care, and not only with the health professionals.6 In this study an educational hand-out has been elaborated, which will be approached in the sixth step for PU prevention.

During patient repositioning the utmost care to avoid friction moves must be taken, which means avoidance to drag the patient on bed sheets. Besides that, whenever possible, the bed headboard shall be elevated up to 30 degrees at the most, once the patient body tends to slide down, consequently causing friction and shearing moves.7,8

Whenever possible, high specificity reactive foam mattresses or pneumatic mattresses shall be considered for risk patients (Braden score ≤ 18) usage, in order to redistribute pressure uniformly. Although it requires larger investments, this measure is cost effective as it tends to reduce hospital stay time as it aims at PU prevention.11 When they are not available, air mattresses might be used. Furthermore, bone prominence areas must be protected by pillows or cushions (examples: knees, heel, ankle).7,11 Specially, heel protection is of extreme importance, whereas it is the most PU incidence site, and the extremities developed ulcers take the longest cicatrization time, rising the hospital stay costs.5,9,11

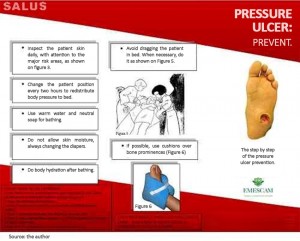

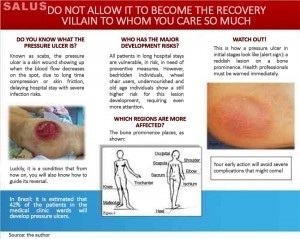

Sixth step: inform the caregiver with the educational hand-out delivery

Literature has corroborated educational measures adoption in PU prevention. Herein, it has been proposed the elaboration of an educational handout about PU, practical and of easy comprehension for caregivers and family members, containing concepts and relevant preventive measures.

This folder (Figures 6 and 7) has been divided in 5 sections: pressure ulcer definition, development risk, most vulnerable bodily areas, early lesion identification, and at last, efficient prevention measures. The handout must be delivered to hospitalized patient caregivers, eliciting their inclusive participation in PU development preventive care. Such action requires the health professional fundamental delivery, with his/her explanation about its content, and a demonstration that it reminds the caregiver of what shall be done in patients benefit along the hospital stay

Figure 6: Educational brochure – outside

Figure 7: Educational brochure – inside

Preventive measures set

Specific preventive measures

At last, it is of fundamental importance to program an individualized prevention plan comprising the six steps previously described, making it easier for the health team to operate. The preventive measures must be risk level specific (based upon Braden scale and the patient subjective assessment) accordingly with the patient risk level met. Nurse clinical subjective assessment must be sovereign concerning the scale, facing existing risk factors and inherent PU development comorbidities, classifying the patient as a high risk one, and as such, establish the specific actions for this subgroup.11,12 Each measure to be implemented with each specific patient group will be described further on.

Low risk patients

Preventive measures for patients within 15 to 18 Braden score: 11,12

- Complete skin inspection every 72 hours, focused on major PU development risk areas;

- Raise awareness in patients and caregivers about preventive measures trough guidance and educational hand-out deliverance, reinforcing PU prevention importance;

- Nursing team or caregivers change patient decubitus every two hours, following the decubitus change schedule;

- Skin hygiene and hydration, keeping it always clean and dry;

- Patient nutritional stage assessment, with a valid and reliable tracking tool, to find the nutritional risk and supply individualized energetic ingestions, based on medical condition and underlying activity level;

- Calcaneus suspension devices usage.

- Moderate risk patients

- Preventive measures for patients within 13 to 14 Braden score: 11,12

- Complete skin inspection every 72 hours, focused on major PU development risk areas;

- Raise awareness in patients and caregivers about preventive measures trough guidance and educational hand-out deliverance, reinforcing PU prevention importance;

- Nursing team or caregivers change patient decubitus every two hours, following the decubitus change schedule;

- Skin hygiene and hydration, keeping it always clean and dry;

- High specificity reactive foam mattresses usage;

- Patient nutritional stage assessment, with a valid and reliable tracking tool, to find the nutritional risk and supply individualized energetic ingestions, based on medical condition and underlying activity level;

- Calcaneus suspension devices usage.

- Moisture handling, with special care for urinary or fecal incontinence patients, and patients with oozing lesions;

- Shearing stress avoidance measures, like the 30 degrees bed inclination angle limit.

- High risk patients

- Preventive measures for patients with ≤ 12 Braden score: 11,12

- Skin daily inspection to reassess risks and early PU detection;

- Raise awareness in patients and caregivers about preventive measures trough guidance and educational hand-out deliverance, reinforcing PU prevention importance;

- Nursing team or caregivers change patient decubitus every two hours, following the decubitus change schedule;

- High specificity reactive foam mattresses usage;

- Calcaneus suspension devices usage.

- Moisture handling, with special care for urinary or fecal incontinence patients, and for patients with oozing lesions;

- Shearing stress avoidance measures, like the 30 degrees bed inclination angle limit.

- Skin hygiene and hydration, keeping it always clean and dry;

- Patient nutritional stage assessment, with a valid and reliable tracking tool, to find the nutritional risk and supply individualized energetic ingestions, based on medical condition and underlying activity level;

- Provide and promote a fit daily ingestion of liquids for patient hydration;

- Dynamic support surfaces usage with a small air release, if possible;

- Pain handling with medicinal treatment assessment whenever necessary.

Discussion

PU development risk population tends to increase, upon factors like aging and the immobility tendency, aside from chronic maladies like diabetes, obesity and vascular diseases.14,15 Due to this change in the population epidemiological profile, there is an urgent need to establish efficient means to prevent PU. A coordinated approach, globally focused on prevention is more promising to gain patient prognostics improvement and cost economy then isolated changes, or modifications exclusively addressing a treatment.14

Intervention strategies include specific changes in PU prevention, combined with educational strategies and handling quality improvement. They point out at the importance of family, caregivers and even more, patient information and guidance. Most of the studies in the literature do demonstrate the positive effects of preventive intervention, when approached with protocol adoption and educational methods.15

Concerning the adoption of risk stratification scales, there are no evidences linking pressure ulcer incidence decrease of them. However, Braden Scale offers the best balance between sensitivity and specificity, aside from being the best risk estimate, more precise than nurses’ clinical judgement on predicting pressure ulcer development. The stratification method has its importance, based on that precision, to early detect and adopt the fittest intervention.16

In the fast guides from EPUAP, NPUAP and PPPIA as of 2014, there are no recommendations to apply Braden scale to stratify patients’ risk level. But, the Ministry of Health PU prevention protocol indicates Braden scale to do so, and guide the specific prevention measures.11

The protocol proposed in this course conclusion research paper includes Braden scale risk stratification upon its better PU risk assessment precision, easy use, its acknowledgement and the Ministry of Health protocol recommendation.12

Literature review shows that objective PU scale assessment tools, although important, are not routinely used by nurse teams to identify pressure ulcer risk in their clinical practice, and they also show that the nurses rely more on their own knowledge and experience than on research evidences to decide PU management.17

Despite the well-known benefits of prophylaxis and the accepted PU prevention directives, they are not consistently used in clinical practice.18 There are many variables, including nursing crews improper attitudes, enhancing PU development. The most common PU prevention barriers reported in the literature are: patient condition, lack of time, lack of personnel, knowledge gaps, lack of routines and care continuity, in addition to pressure redistribution surfaces scarcity in hospitals (high density mattresses, chair cushions).19

It is expected PU incidence decrease with patient prognosis improvement and hospital costs lessening with this protocol adoption at Santa Casa de Misericordia de Vitória Hospital.

Conclusion

Pressure ulcer incidence may reflect the health services quality rendered, once its prevention is easy and low cost. The literature shows that PU treatment costs are substantially greater comparing to its prevention costs.13 Frequently affects bedridden people, suggesting inadequate care, avoidable, with meaningful impacts on health systems economics.

It is observed the importance of the whole health team knowledge, also of the family and / or caregivers involved in this malady control. As such, it is concluded that it is advantageous, not only this protocol implementation, attenuating clinical procedures variability, assuring a more qualified attendance to the patient, but also the divulgation of the educational hand-out, bringing caregivers / family to the pressure ulcer prevention partnership with the health professionals.

References

- Chou R, Dana T, Bougatsos C, Blazina I, Starmer AJ, Reitel K, et al. Pressure ulcer risk assessment and prevention: a systematic comparative effectiveness review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013 Jul;159(1):28-38.

- Reddy M, Gill SS, Rochon PA. A. Preventing pressure ulcers: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006 Aug 23;296(8):974-84.

- Petzold T, Eberlein-Gonska M, Schmitt J. Which factors predict incident pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients? A prospective cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2014 Jun;170(6):1285-90.

- Anselmi ML, Peduzzi M, França Junior I. Incidência de úlcera por pressão e ações de enfermagem. Acta Paul Enferm. 2009;22(3):257-64.

- Bergstrom N, Smout R, Horn S, Spector W, Hartz A, Limcangco MR. Stage 2 pressure ulcer healing in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 Jul;56(7):1252-8.

- Luz SR, Lopacinski AC, Fraga R, Urban CA. Úlceras de pressão. Rev. Bras. Geriatria & Gerontologia. 2010;4(1):36-43.

- Smith ME, Totten A, Hickam DH, Fu R, Wasson N, Rahman B, et al. Pressure ulcer treatment strategies: a systematic comparative effectiveness review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013 Jul 2;159(1):39-50.

- Lyder CH. Pressure ulcer prevention and management. JAMA., 2003 Jan 8;289(2):223-6.

- Lyman V. Successful heel pressure ulcer prevention program in a long-term care setting. J. Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009 Nov-Dec;36(6):616-21.

- 10 European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: quick reference guide. Washington DC: National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, 2009.

- National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Quick Reference Guide. Emily Haesler (Ed.). Cambridge Media: Osborne Park, Australia; 2014.

- Anvisa, Ministério da Saúde, Fiocruz. Protocolo para prevenção de úlcera por pressão, 2013.

- Demarré L, Van Lancker A, Van Hecke A, Verhaeghe S, Grypdonck M, Lemey J, et al. The cost of prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015 Nov;52(11):1754-74.

- Dealey C, Posnett J, Walker A. The cost of pressure ulcers in the United Kingdom. J. Wound Care. 2012 Jun;21(6):261-2, 264, 266.

- Soban LM, Hempel S, Munjas BA, Miles J, Rubenstein LV. Preventing pressure ulcers in hospitals: A systematic review of nurse-focused quality improvement interventions. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2011 Jun;37(6):245-52.

- Pancorbo-Hidalgo PL, Garcia-Fernandez FP, Lopez-Medina IM, Alvarez-Nieto C. Risk assessment scales for pressure ulcer prevention: a systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs.2006 Apr;54(1):94-110.

- Samuriwo R, Dowding D. Nurses’ pressure ulcer related judgements and decisions in clinical practice: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014 Dec;51(12):1667-85.

- Waugh SM. Attitudes of Nurses Toward Pressure Ulcer Prevention: A Literature Review. Medsurg Nurs.2014 Oct;23(5):350-7.

- Silva RC, Figueiredo, NM, Meireles IB. 3.ed. Feridas, fundamentos e atualizações em enfermagem. São Caetano do Sul: Yendis 2007.

Authors

Olavo Corrêa Arêas Saldanha1; Flávio Gusmão Trancoso2; Eduardo Cade Leite3; Marcela Souza Lima Paulo4; Alessandra Tieppo5; Lívia Terezinha Devens6; Fabiano Quarto Martins7; Renato Lirio Morelato8; Hebert Wilson Santos Cabral9

1,2,3 Undergraduate students of the Medical School of the Escola Superior de Ciências da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Vitória – EMESCAM.

4 PhD, Federal University of Minas Gerais – UFMG; Biologist, Professor of the Medical School of the Escola Superior de Ciências da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Vitória – EMESCAM.

5 Specialist in General Practice, Geriatrics and Gerontology, Hospital Administration and Health Economy, Medical Doctor.

6 Specialist in General Practice, Geriatrics and Gerontology, Medical Doctor.

7 Specialist in General Practice and Gastroenterology, Medical Doctor, Professor and Coordinator of the Medicine Internship of General Practice II of the Escola Superior de Ciências da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Vitória – EMESCAM.

8 PhD from the Federal University of Espírito Santo – UFES, Medical Doctor, Professor of the Medical School of the Escola Superior de Ciências da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Vitória – EMESCAM and Coordinator of the Geriatrics Residence of the Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Vitória Hospital – HSCMV.

9 PhD from the Fluminense Federal University – UFF, Medical Doctor, Professor and Coordinator of the Research Center of the Escola Superior de Ciências da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Vitória – EMESCAM.