OMALIZUMAB EFFICACY IN DIFFICULT ASTHMA CONTROL THERAPY IN PEDIATRIC PATIENTS: A LITERATURE REVIEW

Abstract

Objective: To review the literature on advances in the treatment of difficult-to-control severe asthma with the usage of omalizumab in pediatric patients. Method: review of recent literature (2010-2015), using the Pubmed database. Result: the drug reduced exacerbations in frequency and severity, and reduced the need for oral steroids therapy. However, the small population involved and the high cost of the drug makes it a dubious indication for that age range.

Conclusion: It is an effective and safe drug in moderate/ severe uncontrolled asthma; however, studies in the pediatric population remain incipient, suggesting that researches in this field should go on with the development of long-term studies.

Introduction

Asthma has been increasing in incidence and in prevalence along the decades, reaching the top position among the chronicle diseases that most assail the pediatric population. In the UK, 1.1 million children are affected, and among them, 307 suffer from the acute allergic and persistent stage of the illness, remaining uncontrolled despite the best treatment available, characterizing thus the difficult-to-control asthma.1

There are no more reports about asthma as causa mortis in the majority of the countries, but it still increases the morbidity to an important degree.2 Procedures due to asthma in emergency rooms in England reached 79,000 attendances over 2008 to 2009. Among them, 39,000 were children up to 14 years old; and 75% of the cases were avoidable, with a good therapeutic approach and adjoining follow-up.3 Thus, the improvement and the development of new therapies to optimize the treatment and avoid the hospital stays is a must needed effort.

The treatment is administered with inhalable corticoids and long lasting action bronchodilator drugs or leukotriene receptor antagonists in optimized dosages. If the patient remains uncontrolled, oral corticoids or other immunosuppression therapy can be used.3-5

However, oral corticoids present several collateral effects when used, fact that stimulates research and development of new alternative therapies.4,5 To face this demand and to offer support to those who do not respond to the oral corticoid therapy, new drugs are under studies, and one of them is omalizumab.

Omalizumab is an E (IgE) anti-immunoglobulin monoclonal antibody.4 This medicine is of subcutaneous administration. Its dosage is calculated upon the patient body mass index – BMI.4 The drug blocks the interaction between the IgE and its receptors, on the surface of the basophils and of the mast cells.4,6,7 This mechanism reduces the level of serum IgE and the level of its receptors (FceRI) on the basophils, as well as its affinity for them.

This drug administration has been insufficiently studied in the pediatrics range of age, presenting many divergences about it in the literature.3,5,8 Nevertheless, there is a consensus that its usage reduces exacerbations and consequently corticoid therapy. The literature comprising the adult population is far larger, and some few differences regarding effectiveness, benefits over costs and the reduction of specific markers are registered.3-7,9,10 Thus, the objective of this study is to revise the literature about the treatment of difficult control severe asthma with omalizumab in pediatrics patients, knowing the risks and benefits already reported, emphasizing the quality of life of the patients by comparing the therapeutics between adults and the pediatrics population, and assessing the medicine cost-benefit.

Method

Data search was done by consulting the MEDLINE/PUBMED database about the terms “omalizumab” and “asthma” defined by the Medical Subject Headings (MESH Terms). The papers were filtered based on publications from the last five years and that reached the age from birth to 18 years old. 60 papers were found. Those with assessments from 12 years old on were excluded, for inadequacy with the objectives, and those classified as editorials were excluded too, leaving 25 to be reviewed. After a complete and thorough reading of all of them, 17 were selected. They were listed by type of study, highlighting the most relevant aspects in each one, comparing its effectiveness in the youth range of age; and, some difference in specific studies about adults were also demonstrated.

Results

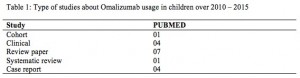

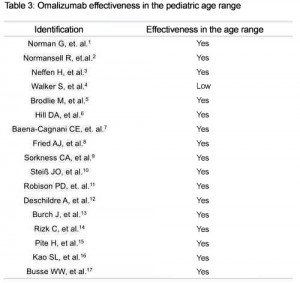

The distribution of paper types is on Table 1 and the synthesis of the results is on Table 2. The Table 3 shows evidences of the medicine effectiveness in the pediatrics range of age. Table 4 reports the differences found regarding the adult range of age presented in each study.

Discussion

The initial treatment is based on inhalable corticoids and long lasting action bronchodilator drugs or leukotriene receptor antagonists in optimized dosages. When the disease remains difficult to control, oral corticoid therapy shall be considered or other immunosuppressive therapies, despite its several collateral effects.3-5 Due to the discomfort with the usage of oral corticoids, other drugs are being studied.

Macrolide antibiotics presented a good safety margin for adults when used for neutrophil asthma control. However, cyclosporine, methotrexate and intravenous immunoglobulin presented low effectiveness.5 Omalizumab usage presented some degree of effectiveness in all the papers herein reviewed. Other monoclonal antibodies, as anti-IL5, anti-IL9, and anti-TNF, presented a variable effectiveness in adults, and there are no studies on the age range of the pediatrics population.5

The action mechanism of these new drugs under studies regards the blocking of interleukins and IgE, related to the allergic asthma physiopathology. It is suggested that the basophils have influence in the start and progression of the allergic inflammation, and that it might be the actuating mechanism for the new therapeutics.6 Omalizumab is a monoclonal anti-IgE antibody approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the allergic asthma treatment. It has been released in the United States in 2003 for patients above 12 years old, suffering from persistent severe asthma and without control gains with optimized dosages of inhalable corticoids. The DG Health and Food Safety of the European Commission released its usage for children above 6 years of age in 2005.4

The administration is subcutaneous. The dosage is calculated upon the patient body mass index.4 The actuating mechanism blocks interaction between IgE and its high affinity receptors on the surface of the basophils and of the mast cells.4,6,7 Thus, the therapeutics reduces the level of serum IgE and the level of its receptors (FceRI) on the basophils, as well as its affinity for them.

Blocking the allergic cascade stops the liberation of cytokines, histamine, tryptase and arachidonic acid metabolites; holding back the allergic process that would be developed by a combination of genetic and environmental factors.7 In face of this fact, the other approach measures are preserved, even if undergoing medication.

Data on how the medicine acts on the circulating basophils are still inaccurate, and diverge somehow. Hill & partners for example, found in their study a reduction on the level of basophils, contributing to a better understanding about the physiopathology of asthma and its mechanisms.6 However, this reduction did not perform the same way in all the patients. Evidences of a possible population that will present a therapeutic lack of response in the future or just an inconsistency in the study? Our interpretation is limited due to the absence of a placebo group.

Even though the LgE level demonstrates to be a good predictor of clinical symptoms, there are evidences of normal level or low level of serum LgE patients with positive responses to omalizumab, which tells us that more studies are required to elucidate this molecule behavior in asthmatics.4

In the majority of the papers, omalizumab has demonstrated effectiveness in the treatment for difficult-to-control asthma. The research done by Walker et al is the exception, with results not demonstrating an important statistical effectiveness in cases of clinically significant exacerbations.1 They concluded that there was a small reduction in the absolute numbers of exacerbations, as well as slight improvement in the quality of life (accordingly with a questionnaire proposed and validated), and in the mortality rate. The reduction of the daily symptoms was not evidenced as well as in the inhalant corticoid therapy. The high costs of the expenditures for the treatment are not justifiable.1

The fact that long lasting collateral effects remain unknown has been mentioned.1 However, Walker et al covered a small sample where most of the individuals were not given the prescribed optimum therapy. Even though, this study levels up with others when it acknowledges the benefits of the reduction of the corticoid therapy for those in constant usage, or say that the same was insufficient.

Several papers give evidence of the reduction on the number of exacerbations, hospital stays and unscheduled doctors’ appointments for patients undergoing treatment with omalizumab. It is also observed the reduction on the use of relief medicines and on the need for oral corticoids.2,3,5,8,10,12,16,17

The usage of inhalant corticoids was also progressively reduced to obtain the appropriate control of the disease.5 These data must be carefully assessed, once the population studied is small and some patients were not being monitored or were, but with insufficient follow up in determined groups. Just a few studies have had the care, when separating the samples, to make sure that the previously proposed therapy was well performed, for instance, they did not report on the wellness of the environmental measures and if the medication was properly administered.

Regarding the oral corticoid therapy, the reviewed studies share the same opinion: omalizumab not only reduces the dosages but also the frequency on its own necessity. Broadlie et al emphasizes a reduction of 15mg, in average, on the daily dosage of oral corticoid, or even its suppression in the difficult control asthma treatment.2 Above all, patients using omalizumab have experienced long periods without crisis after the treatment is over, thus abolishing the relief medication.10

The reduction on oral corticoid therapeutics has valuable aspects eliminating its collateral effects. Among them are hypertension, leonine facies, suprarenal gland suppression, myopathy, growth restriction, obesity, osteopenia and cataract.2

It is worth highlighting that omalizumab addition is the only therapeutic intervention improving the severe allergic asthma control which does not respond to combined treatment with high doses of inhalant corticosteroids, before systemic corticosteroids usage, combined or not with other controlling drugs.5 It corroborates the pediatrician must have theoretical knowledge and clinical practice when using this medication with youth in real need.

One important benefit more from omalizumab is the reduction of seasonal asthma exacerbations.17 The patients using the drug show a reduced number of exacerbations over the weather seasons favoring these events. In general, the peaks occur in spring and in the fall with lesser events in the summer.17

Another fact rising attention in favor of the omalizumab therapy, has been emphasized by Fried et al, observing that, in general, there is a significant statistical improvement in the patient’s quality of life.8

Spirometry is commonly used to follow and diagnose the pathology under study. One of the main figures to be measured is the value of FEV1, allowing measures of the pulmonary function in percentages. In case of flows under 60%, the asthma is considered severe, but values below 80% do demonstrate reduced pulmonary function.3 This parameter presents significant improvements in value for patients undergoing treatment with omalizumab.3,16 Such results were more commonly observed in adults than in young patients. It is an easy explainable fact, once there are limitations in the medical examination for the pediatrics age range: the patient must follow the commands of the professional in charge. That is why the reduction in the pulmonary function is not a parameter to apply in the pediatrics age range, to indicate which medicine shall be used, as it is done for the adult age range.15

In contrast, there are divergences regarding the improvements found with spirometry. Fried and Oettgen mention specifically that the FEV1 results and the expiratory flow peak figures were not altered in patients using omalizumab, and consequently neither was the pulmonary function.8 The statement is confirmed by Busse et al in their report. They say that although clinical improvements and diminishment of other drugs usage, the patients pulmonary function did not improve.17 Nevertheless, the study does not specify how the data was collected.

Omalizumab has also shown advantages in the treatment of other diseases, with high relevance for allergic rhinitis. However, there are evidences of effectiveness in therapies for nasal polyps, cystic fibrosis, atopic dermatitis, spontaneous chronic hives, food intolerance and anaphylaxis. It does demonstrate the increase in the quality of life, the decrease in the symptomatology and also the decrease in relief medication.7,8 It is worth remembering that prescription is based on the failure of other therapeutic measures already adopted. The studies are in the starting phase and in these circumstances, the data is scarce and insufficient for an exact prescription of omalizumab.

When comparing therapeutics between age ranges, it is observed a decrease in the inhalant corticoids dosage in 100% of the pediatrics range, meanwhile in the adult range the results were not quite relevant.4 The drug potential to perform in the pulmonary remodeling process done by asthma is being studied, eliciting a unique potential to prevent and modify the disease physiopathology.7,11 Another relevant information found is a better disease control and a reduced mortality rate among children below 12 years of age.1,12

In spite of the innumerous benefits found, many papers point out at the advantages are not enough to justify the high cost of the omalizumab.1,3,4,10,13 The therapy brings benefits to a small population but in a very important way, and because of that its indication must be precise. The studies about the long time effects are still in development, and thus, these effects may influence the omalizumab indication criteria.

Conclusion

The drug is safe and effective for mild to severe uncontrolled asthma, but studies in the pediatric population remain incipient within the reviewed literature.

The good results already achieved, together with the significant benefits omalizumab may offer, strongly suggests that research must continue on the pediatric population, developing long range random and placebo studies, allowing thus the remaining doubts to be analyzed and the long lasting effects to be studied.

References

1 Walker S, Burch J, McKenna C, Wright K, Griffin S, Woolacott Nl. Omalizumab for the treatment of severe persistent allergic asthma in children aged 6–11 years. Health Technology Assessment. 2011;15(Suppl 1):13-21.

2 Brodlie M, McKean MC, Moss S, Spencer DA. The oral corticosteroid-sparing effect of omalizumab in children with severe asthma. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(7):604-9.

3 Norman G, Faria R, Paton F, Llewellyn A, Fox D, Palmer S, et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of severe persistent allergic asthma: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2013;17(52):1-352.

4 Normansell R, Walker S, Milan SJ, Walters EH, Nair P. Omalizumab for asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 1. Art. No. CD003559. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003559.

5 Neffen H, Vidaurreta S, Balanzat A, De Gennaro MS, Giubergia V, Maspero JF, et al. Asma De Difícil Control En Niños Y Adolescentes Estrategias Diagnóstico-Terapéuticas. Medicina (Buenos Aires). 2012;72(5):403-13.

6 Hill DA, Siracusa MC, Ruymann KR, Tait Wojno ED, Artis D, Spergel JM. Omalizumab therapy is associated with reduced circulating basophil populations in asthmatic children. Allergy. 2014;69(5):674–7.

7 Baena-Cagnani CE, Gomez RM. Therapy with omalizumab in children. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;14(2):149 – 54.

8 Fried AJ, Oettgen HC. Anti-IgE in the treatment of allergic disorders in pediatrics. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2010;22(6):758–64.

9 Sorkness CA, Wildfire JJ, Calatroni A, Mitchell HE, Busse WW, O’Connor GT, et al. Reassessment of omalizumab-dosing strategies and pharmacodynamics in inner-city children and adolescents. J Allergy Clin Immunol: In Practice. 2013;1(2):163–71.

10 Steiss JO, Schmidt A, Nahrlich L, Zimmer KP, Rudloff Sl. Immunoglobulin E monitoring and reduction of omalizumab therapy in children and adolescents. Alergy Asthma Proc, 2012;33(1):77-81.

11 Robison PD, Asperen PV. Newer Treatments in the Management of Pediatric Asthma. Pediatric Drugs. 2013;15(4):291-301.

12 Deschildre A, Marguet C, Salleron J, Pin I, Rittié JL, Derelle J, et al. Add-on Omalizumab in Children With Severe Allergic Asthma: A 1-Year Real Life Survey. Eur Respir J. 2013;42(5):1224–33.

13 Burch J, Griffin S, McKenna C, Walker S, Paton J, Wright K, Woolacott N. Omalizumab for the Treatment of Severe Persistent Allergic Asthma in Children Aged 6–11 Years. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30(11):991-1004.

14 Rizk C, Ring A, Santucci S, MacLusky I, Karsh J, Yang WH. Omalizumab treatment in a child with severe asthma and multiple steroid-induced morbidities. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109(3):222–3.

15 Pite H, Gaspar A, Paiva M, Leiria-Pinto P. Omalizumab under 12 years old: Real-life Practice. J. Aler. 2012;41(2)133-6.

16 Kao SL, Yu HR, Kuo HC,Tsui KY, Wu CC, Chang LS, et al. Higher levels of soluble Fas ligand and transforming growth factor-b after omalizumab treatment: A case report. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. 2012;45(1):69-71.

17 Busse WW, Morgan WJ, Gergen PJ, Gergen PJ, Mitchell HE, Gern JE , et al. Randomized Trial of Omalizumab (Anti-IgE) for Asthma in Inner-City Children. N Engl J Med.2011;364(11):1005-15.

Attachments

Source: author. Note: translated.

Source: author. Note: translated.

Source: author. Note: translated.

Authors

Gillyane Nico Cremasco1; Gillyane Nico Cremasco2; Gustavo Carreiro Pinasco3; Aline Rocha Camporez4; Fabrício Smiderle Pereira5*

1,2 Undergraduate Student, Superior School of Sciences of Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Vitória – EMESCAM.

3 Specialist – Resident Doctor at the Federal University of São Paulo – UNIFESP, Brazil.

4 Specialist in allergy and immunology by the Brazilian Association of Allergy and Immunology. Professor of Medical Clinic III at Multivix.

5 Specialist – Resident Doctor in Pediatrics at Hospital Infantil Nossa Senhora da Glória – HINSG, Vitória, Brazil.