COW MILK ALLERGY: STATE OF ART

Abstract

Objective: To check the state of art in the steps taken in pediatric practice in cow ‘s milk allergy . Method: review in the Pubmed database 2005 to 2015. Cow ‘s milk allergy is the main food allergy in childhood. The diagnosis is still difficult to achieve in clinical prac-tice and the lack of standardization of laboratory research a challenge. The importance of correct driving in suspected or confirmed diagnosis is seen in the large potential impact on growth and development of children subjected to food restriction.

Keywords

Child; Milk Hypersensitivity; Food Hypersensitivity

Introduction

Food allergy and the so called intolerance have caused perplexity in the medical practice. Food allergy or hypersensitivity involves the immunological response of the body to heterologous proteins, whereas food intolerance, for example, lactose intolerance – involving lactase deficiency –, is not related with hypersensitivity 1.

Food allergy prevalence in children ranges from 6% to 10%2,3,4 and it most frequently involves food such as cow milk, egg, wheat, corn, soybeans, seafood and peanuts5,6. Allergy to cow milk protein (ALV) is the most common in children (prevalence between 2% – 3%), among all food allergies 7,8,910,11,12,13. Fifty percent of allergy cases are diagnosed in the first month of life. Cow milk protein desensitization often takes places as age advances, thus, allergy reduces approximately 75% in the first three years of life and 90% at the 6th year11.

Correct ALV diagnosis is important to prevent the inappropriate use of restrictive diets that can bring harm to child development11,13,14,15,16,17,, or the special and expensive formulas unaffordable by most families. The present research aims to verify the state of art on the steps taken in pediatric practice regarding cow milk protein allergy.

Method

Research Strategy

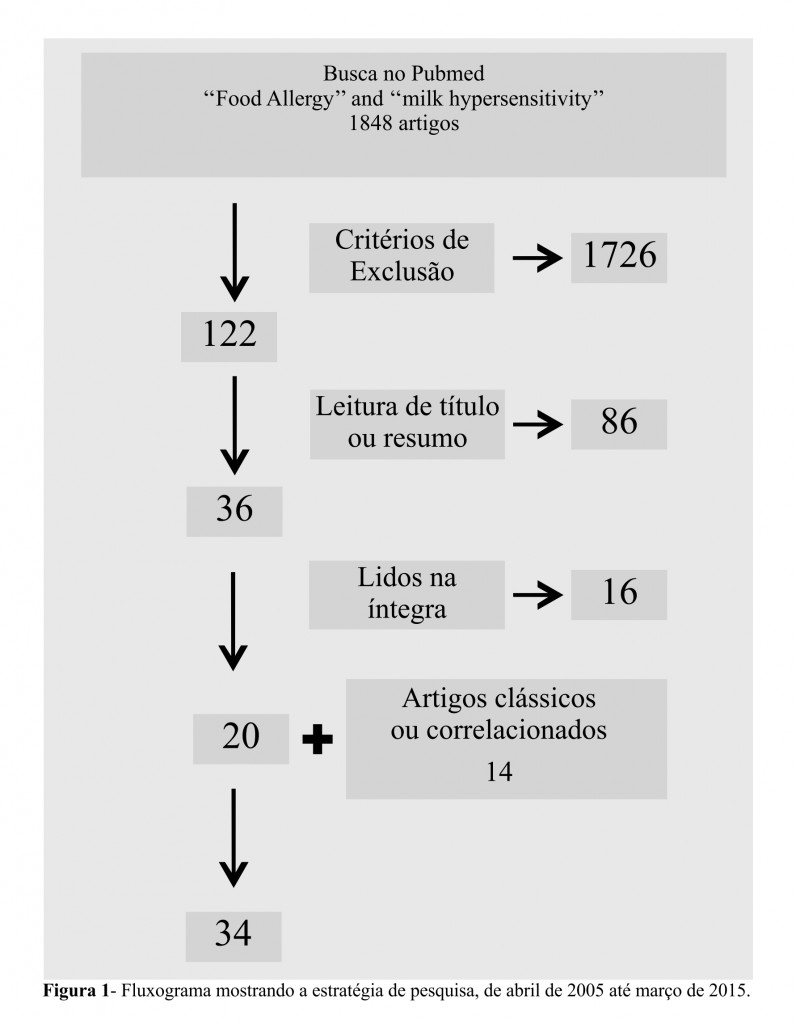

The revision was made in Pubmed / Medline database and were considered papers published between 2005 and 2015. Publications were selected according to the terms: “Milk hypersensitivity” and “Food Allergy”, which were defined by the Medical Subject Headings (MESH). The texts were filtered by publication date, language (English, Portuguese and Spanish), age (birth to 18 years old) and other inclusion and exclusion criteria. All steps are shown in Figure 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Original articles, related classic articles and meta-analyses and guidelines involving clinical studies with humans were considered to be the objects of study. Fast communications, letters to the editor, incomplete texts and experimental animal studies were excluded.

Selection Strategy

Unrelated articles were selected by title reading. Works not related with the topic were deleted after abstract reading. The remaining articles were completely read and selected by relevant association with the subject. Classical and correlated articles that did not appear in the search were included due to the direct search done for renowned and specialized group of authors. The two researchers analyzed the articles and agreed on the inclusion of the selected ones.

Immunology And Clinical Manifestations

After cow milk ingestion, its protein is phagocytosed by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) located in the intestinal mucosal or in the lungs. APCs process the antigen and present their epitopes to the T helper lymphocyte 3. Tolerance will possibly result from the regulatory action of interleukin (IL) – 10 on the Th2 response. The increased levels of the specific cow milk protein IgG4 will be found in response to IL-10 and it reduces IgE levels, fact that result in the development of tolerance mechanisms18.

Allergy to cow milk protein (CMA) may due to the immune reaction of IgE (immunoglobulin) mediated, the mixed reaction (IgE-mediated and cell) or a non-mediated IgE reaction11,19.

The IgE-mediated reaction is the most common immune response17. The sensitization phase begins after the first contact with the antigen: T lymphocytes secrete Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 and it stimulates IgE by the B lymphocytes. IgE binds to the surface of the mast cell, thus stimulating histamine release. After a new contact with the allergen, the sensitized body triggers the immediate hypersensitivity reaction effector phase (type I) within the first 12 – 24 Hours3. Immediate reactions typically occur a few minutes or up to 2 hours after exposure 11,20. It is characterized by acute inflammatory immune response at the site exposed to the allergen. Such response is also regulated by Th2 T lymphocytes that stimulate effector cells’ – neutrophils and eosinophils – maturation and recruitment in the antigen exposed site 3.

There is the involvement of immunoglobulin E, T lymphocytes and pro inflammatory cytokines in mixed reactions. Eosinophilic esophagitis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, atopic dermatitis and asthma are examples of this group1,11.

Non-IgE-mediated manifestations include cell mediated hypersensitivity reactions that possibly involve cytotoxic and immunocomplex reactions. This group presents late submission manifestations with chronicity tendency1. Such manifestations usually occur 48 hours after exposure to the allergen and they may have onset delay up to 1 week11.

Most children present symptoms on the following systems: gastrointestinal (50% – 60%), skin (50% – 60%) and respiratory (20% – 30%)16, when there are two or more affected systems there is greater chance of CMA11. Neurological and cardiovascular symptoms may also be found, but they are more often related to anaphylaxis1. The most common clinical manifestations are shown in Table 1.

Diagnosis

Clinical and epidemiologic evaluation play a key role in diagnosing adverse reactions to food11,16,17,19,20. Family history of allergy among first-degree relatives increases CMA risk. Allergy risk, in general, increases in approximately 20-40% in case of any history of atopy among first-degree relatives and it can raise up to 70% if both parents are atopic16,21.

According to a systematic Cochrane review (2006), children exposed to cow milk or soy-based formulas before 6 months of age are at higher risk of developing allergy or food intolerance22. The incidence of CMA is lower in children fed only with breast milk in comparison to those who were formula-fed before 6 months of age16,23.

Some diagnostic tests can be performed after the clinical suspicion. The determination of specific IgE has been widely used in cases of type I hypersensitivity. IgE serum levels are indicative of the protein presence in a food, but they do not define if a particular food is causing the symptoms. One should always associate the clinical history and the test results 5,11,17. The tests can help indicating the food to be assessed in oral challenge tests. However, there can also be cross-reactions with epitopes from other proteins.

The skin immediate hypersensitivity (skin prick test) is another usual test to assess allergen sensitization11. This test shows 95% negative predictive value and is easy to perform. However, it can only evaluate IgE-mediated reactions. Therefore, it is not useful in cell-mediated reactions1. The patch test – in which adhesives with specific antigens are adhered to the patient’s skin – assesses the cellular hypersensitivity reaction7,18. Nevertheless, it still plays limited role in CMA diagnosis due to lack of standardized preparation and to the implementation of the antigen. There is no superiority between total IgE determination and intradermal test 11.

Oral challenge tests are considered the main way to establish CMA diagnosis. Double-blind and placebo-controlled oral food challenges are the gold standard for this diagnosis11,13,17. However, an open oral challenge test (patient and physician aware) is used due to embodiment difficulties1,11.

Possible allergenic food is excluded from the patient’s diet as a means of examination. After 2-4 weeks of exclusion the food is offered to the patient again and it is done in an environment where support can be offered if any adverse event takes place5,9,16.

The procedure begins with the patients physical examination to compare possible changes that may appear during the test 16. The doctor humidifies the child’s lips with a formula containing whole cow milk protein or in natural cow milk; after 30 minutes, 10 ml is administered via a progressive swelling scheme every 20-30 minutes until a 150 minutes round is completed25. The patient should be observed for 2 hours after the last administration and examined again before being cleared. The doctor must focuses on responses from the respiratory and the skin systems.

The oral challenge test should be avoided in cases of clear history of immediate reaction to cow milk protein added to the specific positive IgE due to increased anaphylaxis risk11.

Treatment

As soon as the CMA diagnosis or its strong suspicion is established, the total exclusion of the heterologous protein from child’s diet must be indicated 4,11,13.

Only 0.5% of exclusively breastfed children have clinical manifestations associated with cow milk protein allergy sensitized via human milk supplied by the mother who consumes cow milk7. Most of these symptoms are mild or moderate16. The exclusion of cow milk and its derivatives from the mother’s diet can be indicated in this case only23,26,27.

The European Society of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Pediatric (ESPGHAN)11 recommended the introduction, after 6 months of age, of extensively hydrolysed soya protein, cow milk or basic amino acids based formulas after six months of age as treatment, but it does not recommend the use of isolated soy protein-based formulas11,28. The two formulas are also effective in reducing symptoms. The amino acids formula is more commonly applied in cases of reaction to extensively hydrolysed protein formulas4,11,28,29. However, the American Academy of Pediatrics suggests isolate soy protein formulas to IgE-mediated allergies; however only after 6 months of life 30.

The Brazilian Society of Pediatrics (SBP) considers the two possibilities as treatment options and recommends their use in suspected non IgE mediated ALV and in IgE mediated CMA in children under 6 months old who are exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life. In case the two options are not possible, it is possible to exclusively introduce the hydrolyzed formula. As for IgE-mediated CMA suspicion in 6 months old children or older, soy protein-based or extensively hydrolyzed formulas can be introduced1.

Infants should be away from cow milk for at least six months during the treatment. Such period may be extended to 9 or 12 months and, in case of severe immediate reaction, it must be extended to 18 months before a new oral challenge test is done11.

Nutritional Guidelines

The nutritional treatment aims to prevent disease progression, the worsening of signs and symptoms and to enable child growth and development. Therefore, nutritional guidance in cow milk protein allergy is an important step in the treatment.

The child’s nutritional, socio-cultural and economic status should be assessed. A food recall of at least four days – including the weekend if necessary – should be performed. This is the way to have an idea about the child’s diet to avoid an insufficient caloric intake for the age1.

Micronutrients intake should be adequate to avoid specific nutritional deficiencies and enable proper metabolism 31. In a recent study Seppo et al have demonstrated adequate zinc, iron, riboflavin and vitamin E intake by children who were introduced to protein based formula and soybean hydrolysate protein. There was no correct daily calcium intake, fact that requires oral supplementation32.

Nutritional assessment and the correct feeding should be performed in sequence in order to avoid too restrictive diets or exclusion diet transgressions. Families should receive proper guidance on the acquired processed foods; they should be informed on how to read labels and understand the terms found in the nutritional information that may indicate milk traces or any milk component such as caseinate, whey, lactoglobulin, casein and lactoferrin. These guidelines can avoid unintentional diet exclusion transgression13.

Prophylaxis

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months of life and it takes into account not just the food allergy prevention aspects, but also other nutritional aspects such as prevention of respiratory and intestinal infections. The introduction of supplementary feeding is not recommended before 6 months of age by the WHO 33, but in recent statements the American Academy of Pediatrics discussed the possibility of starting it between the 4 and 6 months of age6. During this period there would be a “window period’ when contact with food would promote T cell immune modulation response and it would lead to food tolerance however cow milk introduction is just recommended from the 1th year of age on27.

Studies have shown decreased incidence of peanut, egg and fish allergy in populations where these foods were introduced at one year and six months of age. The American, European and Canadian Academies of Pediatrics suggest solid food introduction after 4 to 6 months of life 6,11,34.

Cow milk protein exclusion from the mother’s diet during lactation as CMA primary prevention measure is not recommended. Recent findings suggest that restrictions on maternal diet during pregnancy and lactation do not alter the possibility of developing sensitization processes and food allergy in childhood23,26,27,34.

Differently from what is observed in the clinical practice, isolate soy protein formulas are not hypoallergenic16, as well as goat, sheep and other mammal’s milk1, and they should not be used in food allergy prophylaxis11,22,27,29,31. Soy protein allergic reactions have been reported in 30% to 50% of infants with CMA31.

References

- Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria; Associação Brasileira de Alergia e Imunologia. Consenso Brasileiro sobre Alergia Alimentar. Rev Bras Alerg Imunopatol. 2008;31(2):64-89.

- Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food Allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):470-5.

- Herz, U. Immunological Basis and Management of Food Allergy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:54–7.

- Niggemann B, von Berg A, Bollrath C, Berdel D, Schauer U, Rieger C, et al. Safety and efficacy of a new extensively hydrolyzed formula for infants with cow’s milk protein allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19:348–54.

- Niggemann B, Beyer K. Diagnosis of food allergy in children: Toward a standardization of food challenge. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:399-404.

- Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW and the Committee on Nutrition and Section on Allergy and Immunology. Effects of Early Nutritional Interventions on the Development of Atopic Disease in Infants and Children: The Role of Maternal Dietary Restriction, Breastfeeding, Timing of Introduction of Complementary Foods, and Hydrolyzed Formulas. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):183-91.

- Brill, H. Approach to Milk Protein Allergy in Infants. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1258-64.

- Meyer, R. New Guidelines for Managing Cow´s Milk Allergy in Infants. J Fam Health Care. 2008;18(1):27-30.

- Husby, S. Food Allergy as Seen by a Paediatric Gastroenterologist. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47(2):49–52.

- Vieira MC, de Morais MB, Spolidoro JVN, Toporovski MS, Cardoso AL, Araujo GTB, et al. A Survey on Clinical Presentation and Nutritional Status of Infants with Suspected Cow’s Milk Allergy. BMC Pediatrics. 2010;10:25.

- Koletzko S, Niggemann B, Arato A, Dias JA, Heuschkel R, Husby S, et al. Diagnostic Approach and Management of Cow’s-Milk Protein Allergy in Infants and Children: ESPGHAN GI Committee Practical Guidelines. JPGN. 2012;55(2):221-29.

- Pajno GB, Caminiti L, Salzano G, Crisafulli G, Aversa T, Messina MF,et al. Comparison between two maintenance feeding regimens after sucessful cow’s milk oral desensitization. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24: 376–81.

- Dambacher WM, de Kort EHM, Blom WM, Houben GF, de Vries E.Doubled-blind placebo-controlled food challenges in children with alleged cow’s milk allergy: prevention of unnecessary elimination dites and determination of eliciting doses. Nutrition Journal. 2013, 12:22. Available from: http://www.nutritionj.com/content/12/1/22.

- Sampson. Update on food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(5):805-19.

- Martorell A, Plaza AM, Boné J, Nevot S, García Ara MC, Echeverria L, et al. Cow’s milk protein allergy. A multi-centre study: clinical and epidemiological aspects. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2006;34(2):46-53.

- Vandenplas Y, Brueton M, Dupont C, Hill D, Isolauri E, Koletzko S, et al. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Cow’s Milk Protein Allergy in Infants. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:902-8.

- Gushken AKF, Castro APM, Yonamine GH, Corradi GA, Pastorino AC, Jacob CMA. Double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges in Brazilian children: Adaptation to clinical practice. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2013;41(2):94-101.

- Sommanus S, Kerddonfak S, Kamchaisatian W, Vilaiyuk S, Sasisakulporn C, Teawsomboonkit W, et al. Cow’s milk proteína allergy: immunological response in children with cow’s milk protein tolerance. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2013;32:171-7.

- Shek LPC, Bardina L, Castro R, Sampson HA, Beyer K. Humoral and cellular responses to cow milk proteins in patients with milk-induced IgE-mediated and non-IgE mediated disorders. Allergy. 2005;60:912-9.

- Caldeira F, Cunha J, Ferreira MG. Alergia a Proteínas de Leite de Vaca: um Desafio Diagnóstico. Acta Med Port. 2011;24:505-10.

- Osborn David A, Sinn John KH. Formulas containing hydrolysed protein for prevention of allergy and food intolerance in infants. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD003664.

- Osborn DA, Sinn J. Soy formula for prevention of allergy and food intolerance in infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Oct 18;(4):CD003741.

- Zeiger, RS. Dietary Aspects of Food Allergy Prevention in Infants and Children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;1(30):77-86.

- Cocco RR, Camelo-Nunes IC, Pastorino AC, Silva L, Sarni ROS, Filho NAR, et al. Abordagem laboratorial no diagnóstico da alergia alimentar.Rev Paul Pediatr. 2007;25(3):258-65.

- Correa FF, Vieira MC, Yamamoto DR, Speridião PG, de Morais MB. Teste de desencadeamento aberto no diagnóstico de alergia à proteína do leite de vaca. J Pediatr. 2010;86(2):163-166.

- Thygarajan A, Burks AW. American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations on the effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20(6):698-702.

- Heine RG, Tang MLK. Dietary approaches to the prevention of food allergy. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11:320-28.

- Vandenplas Y, De Greef E, Hauser B, Paradice Study Group; Paradice Study Group. An extensively hydrolysed rice protein-based formula in the management of infants with cow’s milk protein allergy: preliminary results after 1 month. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99:933–6.

- Lifschitz, C. Is There a Consensus in Food Allergy Management? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:58–9.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition: Hypoallergenic infant formula. Pediatrics 2000;106:346-9.

- Agostoni C, Axelsson I, Goulet O, KoletzkoB, Michaelsen KF, Puntis J, et al. Soy Protein Infant Formulae and Follow-On Formulae: A Commentary by the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:352-61.

- Seppo L, Korpela R, Lönnerdal B, Metsäniitty L, Juntunen-Backman K, Klemola T, et al. A Follow-up Study of Nutrient Intake, Nutritional Status and Growth in Infants with Cow Milk Allergy Fed either a Soy Formula or an extensível Whey Formula. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:140–5.

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Guia alimentar para crianças menores de 2 anos/Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Atenção à Saúde. Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde – Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2005.

- Chin B, Chan ES, Goldman RD. Early exposure to food and food allergy in children. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:338-9.

Attachments

| Table 1 – Key Signs and Symptoms in Allergy to Cow’s Milk Protein | |||||

| Affected Systems | Infants and children | Older children | IgE-Mediated | Non-IgE-mediated | Immediate reaction (within minutes up to 2 hours) |

| gastrointestinal | dysphagia

gastroesophageal reflux Colic, abdominal pain vomiting Anorexy, refusal to feed Diarrhea with or without loss of protein or blood constipation with or without hyperemia perianal Reduction in motility Fecal occult blood |

dysphagia

gastroesophageal reflux dyspepsia Nausea, vomiting Anorexy, early satiety Diarrhea with or without loss of protein or blood constipation abdominal pain Fecal occult blood |

Allergy oral manifestations

Nausea, vomiting colic diarrhea |

gastroesophageal reflux

enteropathy transient Enteropathy protein-losing colitis constipation Difficulty growth |

vomit |

| Respiratory Tract | runny nose

wheezing Chronic cough (noninfectious cause) |

runny nose

wheezing Chronic cough (noninfectious cause) |

rhinoconjunctivitis

Wheezing Chronic cough (noninfectious cause) Laryngeal edema Suppurative otitis media |

pulmonary hemosiderosis

(Heiner syndrome) |

Cough or stridor

Difficulty breathing |

| Skin | Urticaria (without other defined causes)

Atopic eczema Angioedema (swelling of the lips or eyelids) |

Urticaria (without other defined causes)

Atopic eczema Angioedema |

atopic dermatitis

hives angioedema |

skin rash

atopic dermatitis |

hives

angioedema |

| General | Symptoms of shock with severe metabolic acidosis, vomiting and diarrhea (food protein-induced enterocolitis) | Anafilaxia | anaphylaxis | anaphylaxis

Food protein induced enterocolitis |

|

Source: Brill, 2008; Koletzko,2012.

| Table 2 – carrying out instructions from Nettle Oral Test |

| Establishing cow milk protein allergy diagnosis after excluding it from the child’s diet |

| Many suspect foods |

| Previous anaphylactic type reaction |

| Attempt to establish the cause and effect relationship between allergen and symptoms |

| Suspected allergic reactions not mediated by IgE or its mixed form |

Source: Cocco, 2007.

Authors

Gustavo Carreiro Pinasco: Pediatrician and Nutrologist with Master Degree in Public Health at Faculdade de Medicina do ABC (FMABC). Member of the Studies Design and Scientific Writing Laboratory at FMABC (Pediatrics Professor at School of Sciences of Santa Casa de Misericórdia,Vitória (EMESCAM))

Elizandra Cola: Medical Student at Federal University of Espírito Santo

Valmin Ramos da Silva: Phd In Pediatrics UFMG. Professor Of Master Degree In Health Public Policies And Local Development, (Emescam).

Katia Valéria Manhabusque: Master Degree In Pediatrics At Universidade De São Paulo (Usp). (Pediatrics Professor At School Of Sciences Of Santa Casa De Misericórdia,Vitória (Emescam).

Luiz Carlos de Abreu: PhD In Public Health. Full Professor Of Stricto Sensu Program At Faculdade De Medicina Do Abc (Fmabc), Santo André, São Paulo. Member Of The Studies Design And Scientific Writing Laboratory At Fmabc.