GOOD SYNDROME – A CASE REPORT

Abstract

Good Syndrome is the association between thymoma and immunodeficiency presented through recurrent infections and immunologicalevaluation as well as through the reduction or absence of B lymphocytes, hypogammaglobulinemia and defects in cellular immunity. We herein study the case of a 58-year-old woman who presented recurrent sinusitis, pneumonia and previous disseminated strongyloidiasis. Chest tomography showed a mediastinal mass occupying the thymic space and, subsequently, bronchiectasis in the upper lobes. Excision of the lesion and histopathologic examination confirmed thymoma. Hypogammaglobulinemia and B lymphocyte reduction was observed at immunological investigation. Evaluate T and B lymphocytes and immunoglobulins measurement should be considered part of routine evaluation in thymona patients because it allows the early identification of the syndrome.

Keywords

Thymoma; Agammaglobulinemia; Immunologic Deficiency Syndromes; Infection

Introduction

Thymoma and immunodeficiency association was first described by Robert Good in 1954 and subsequently called Good Syndrome. 1 It consists of a rare condition that most commonly occurs in adults aged 40 to 70. It is characterized by the presence of thymoma and repeating infectious conditions. Its immunologic assessment shows the reduction or absence of B cells in peripheral blood, hypogammaglobulinemia and cell-mediated immunity malfunction.2 The syndrome occurs in 7 to 13% of adult hypogammaglobulinemic patients.

The incidence of hypogammaglobulinemia in thymoma patients is 6-11%.4 Table 1 describes the syndrome, its clinical manifestations and complications, laboratory findings and treatment options.

Table 1: Good Syndrome important features *

| DEFINITION | THYMOMA BY IMMUNODEFICIENCY |

| Clinical manifestations and complications | Increased susceptibility to bacterial infections, especially to encapsulated and opportunistic organisms (viruses and fungi); to autoimmune diseases such as myasthenia gravis, neutropenia, diabetes mellitus, polymyositis, pure red cell aplasia and anemia. |

| Laboratory findings | Hypogammaglobulinemia, reduction or absence of B cells, lymphopenia CD4 +, low T cells’ proliferative response to mitogens. |

| Treatment Options | Thymoma resection whether malignant, invasive or obstructive; immunoglobulin replacement; antibiotic as appropriate; immunosuppressive agents, whether there is presence of autoimmune disease.® |

* Adapted by AGARWAL; CUNNINGHAM-RUNDLES, 2007.2

The present report describes the clinical case of a Good Syndrome patient followed by literature review.

Case report

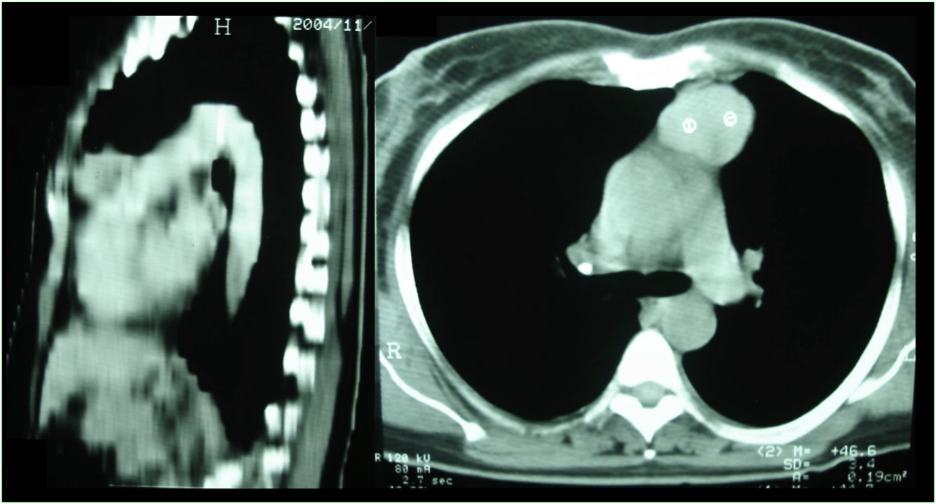

A 58 year-old female patient started presenting recurrent respiratory infections (sinus infections and pneumonia) at age of 55. In the same year she was hospitalized for seven days due to disseminated strongyloidiasis. Radiological assessment showed mass lesion with soft tissue density in the anterior mediastinum occupying the thymic store (Figure 1). In addition to radiotherapy, the patient underwent surgery to remove the mass; the histopathologic examination detected thymoma.

The patient had previous history of eosinophilia since childhood and had received several anti-parasitic treatments, particularly after the persisting finding of the parasite Strongiloides stercoralis and the protozoa Blastocystis hominis in her fecal samples. She had also presented recurrent sibilance due to the use of inhaled corticosteroids associated with long-acting beta2-agonist.

Two years after thymectomy, the patient was indicated to immunological assessment. On this occasion, the patient had already presented bronchiectasis in the upper lobes of the right and left lung. The immunological analysis showed hypogammaglobulinemia and reduced subpopulation of B lymphocytes (Table 2), thus monthly intravenous gammaglobulin replacement was indicated.

Table 2 – Laboratory tests

| Hemogram

Red serie Leucogram Platelet |

Hb 11.1 g / dl Hct 33.8% CM 87.9 fl

Leuc 14.100 / mm3 (1% bast, 57% sec; 22% eos; 14% lymphomas; 6% Mono). 806.000 / mm3 |

| Reticulocytes | 0.5% |

| Lymphocytes subpopulation

CD4 RV (476-1136) CD8 RV (248-724) CD4/CD8 CD3 RV (844-1943) CD19 RV (138-544) |

35.3% (697/ mm3)

38.8% (766/ mm3) 0.9 78% (1540/ mm3) 0.2% (4/ mm3) |

| Immunoglobulins

IgG RV (739-1390) IgA RV (84-354) IgM RV (81-167) IgE RV (<90) |

169 mg/dl

46 mg/dl 10 mg/dl 3 UI/ml |

RV – Reference value

Discussion

Thymoma and hypogammaglobulinemia association was defined as a subtype of the common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), however, the reduced number of peripheral B cells noticed in the Good Syndrome made it be classified as a distinct immunodeficiency, since it was found that CVID is an impediment to B cells maturation rather than a sharp reduction, as it is seen in this syndrome.5,6,7,8

It is a rare condition with few cases reported in the literature. KELESIDIS &YANG (2010), in a systematic review, described clinical, laboratory and immunological findings from 152 patients – 47% of them were European.8 Symptoms onset are slow; patients’ mean age is 56; the symptoms begin between 29-75 years old; and diagnosis takes place between 41-79 years old. There is only one report in the pediatric age group;9,10,11,12 there is no significant difference between genders.

Thymomas are slow-growing tumors, corresponding to 20-30% of the mediastinal masses in adults; it appears on chest radiographies as a lobulated clear-cut mass.12 It may, however, not be displayed in radiographic examination in approximately 20-24% of the cases; thus chest tomography may be more sensitive.13 They are typically an incidental asymptomatic finding, however one third of the patients may present chest pain, cough or dyspnea due to compression over the tumor or its invasion.12 Most dried thymomas in the Good Syndrome are benign and encapsulated, 75% of them appear in the fusiform type. Metastasis is uncommon, although often associated with systemic and autoimmune diseases such as pure red cell aplasia, hypogammaglobulinemia, pancytopenia, collagen disease and myasthenia gravis.8,13,14,15 Thymoma’s resection does not reverse the immunological abnormalities and it suggests that hypogammaglobulinemia is not directly caused by thymoma, but actually by autoimmune or immunoregulatory processes, as it will be discussed later. Immunodeficiency may precede or occur after thymoma is diagnosed. There are infectious symptoms and hypogammaglobulinemia reports starting up to18 years after thymectomy.16 In the case herein described, the patient developed recurrent infectious condition, with possible immunological impairment, before the mediastinal mass was detected and resected.

The main immunological findings in Good Syndrome showed hypogammaglobulinemia and B cells absence or reduction, possible abnormality in the CD4 / CD8 ratio, CD4 T cell lymphopenia and reduction of T cell response to mitogens. 3,17 The patient reported extremely low mature B cell levels – as described in 87% of the cases reported in the literature – and absence of pre-B cells in bone marrow samples from some patients with this syndrome.3 Data available about abnormalities found in the counting and functioning of T cells in the publications are limited. Although reported in a big number of patients, the percentage of T cells and the CD4 / CD8 ratio were normal in the herein investigated patient. The lymphoproliferative response of lymphocytes compared to mitogens had not been evaluated.

The pathogenesis of this thymoma and antibody deficiency association is unknown. There are, however, hypotheses suggesting pre-B cells imprisonment, impediment on the erythroid maturation of myeloid precursors, disorders in the differentiation of B cells due to humoral factors derived from bone marrow and T cell dysfunction causing impairment in the strain definition of B-cells.6,18

Infections presented by the patients result from defects in humoral and cellular immunity. TARR et al., reviewed the infectious processes and isolated microorganisms in 51 Good Syndrome cases; they described recurrent upper and lower respiratory tract infections as the most frequent ones.10 The encapsulated bacteria were the most isolated pathogen: Haemophilus influenza, in 24% of cases; and Streptococcus pneumonia, in 8%. Bronchiectasis was found in 7 cases in this series, with the isolation of Pseudomonas spp, Klebsiella spp and other Gram negative. Giardia lamblia and enteric pathogenic bacteria (Salmonella spp, Campylobacter jejeuni) were found in patients with chronic diarrhea. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis was diagnosed in 24% of the cases. Viral infections were found in 40% of the patients, and cytomegalovirus was the most common pathogen (24% of the cases).7 The herein reported patient had infectious symptoms in the respiratory tract, probably caused by encapsulated germs, which are the most commonly germs involved in this type of infection. However, there was no isolation in none infectious episode. So far, the patient had not presented any opportunistic infection, possibly because she did not show T-cell dysfunction.

The persistent intestinal infestation by Strongyloides stercoralis found in the current case study was not corroborated by other Good Syndrome accounts, except for a national article that reported the association between thymoma and severe strongyloidiasis.19 The assessed patient in this study was a 59 years old male who had eventually died six days after admission due to severe respiratory infection accompanied by numerous episodes of diarrhea and severe anemia. The presence of encapsulated thymoma was found at necropsy as well as intense inflammatory infiltration in the small and large intestine with the presence of rhabditoid larvae and strongyloid eggs located in the crypts. Due to the rapid evolution, hypogammaglobulinemia had not been proved and there was no description about the total number of lymphocytes; although, low levels of globulins were found in the protein electrophoresis. Strongyloidiasis association and other antibody defects such as CVID and IgA deficiency are also described as rare cases, since hyperinfection conditions with risk of parasite dissemination are often associated with cellular immunity impairment and with patients who systematically take corticosteroids.10

Thymoma treatment includes thymus resection to prevent local invasive growth and metastasis, as well as the combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy in cases of advanced tumor disease (stage 3 or 4).16 As in other hypogammaglobulinemia cases, antibody deficiency requires gamma globulin replacement, since it leads to better control of infection incidence, thus reducing hospitalization and antibiotic administration.17 The prognosis, however, seems to be less favorable in comparison to that of patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia and CVID.9,18 The main causes of death result from infection, autoimmune disease or haematological complications.3

Thymoma and immunodeficiency association is rare, although several reports have contributed to better understanding the disease. The immunological research, which includes T and B cell subpopulation assessment and immunoglobulins quantification, should be considered in routine diagnostic evaluation of thymoma patients, in order to provide early identification of Good Syndrome patients.

Figure 1 – Computed chest tomography showing mass in the anterior mediastinum to the left, taking thymic store topography and measuring approximately 5.0 x 4.0 cm in their major axes.

References

- Good RA. Agammaglobulinemia: a provocative experiment of nature. Bull Univ Minn. 1954;26:1-19.

- Agarwal S, Cunningham-Rundles C. Thymoma and immunodeficiency (Good syndrome): a report of 2 unusual cases and review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;98(2):185-90.

- Kelleher P, Misbah SA. What is Good’s syndrome? Immunological abnormalities in patients with thymoma. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56(1):12-6.

- Rosenow EC, Hurley BT. Disorders of the thymus. A review. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144(4):763-70.

- Bonilla FA, Bernstein IL, Khan DA, Ballas ZK, Chinen J, Frank MM et al. Practice parameter for the diagnosis and management of primary immunodeficiency. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;94(5 Suppl 1):S1-63.

- Joven M, Palalay MP, Sonido C. Case report and literature review on Good’s syndrome, a form of acquired immunodeficiency associated with thymomas. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2013;72 56–62.

- Notarangelo L, Casanova JL, Conley ME, Chapel H, Fischer A, Puck J et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: an update from the International Union of Immunological Societies Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases Classification Committee Meeting in Budapest, 2005. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(4):883-96.

- Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, Casanova JL, Chatila T, Conley ME, Cunningham-Rundles C, et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: an update on the classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies expert committee for primary immunodeficiency. Front Immunol. 2014;5:162.

- Kelesidis T, Yang O. Good’s syndrome remains a mystery after 55 years: a systematic review of the scientific evidence. Clin Immunol. 2010;135:347-63.

- Tarr PE, Sneller MC, Mechanic LJ, Economides A, Eger CM, Strober W et al. Infections in patients with immunodeficiency with thymoma (Good syndrome). Report of 5 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80(2):123-33.

- Sicherer SH, Cabana MD, Perlman EJ, Lederman HM, Matsakis RR, Winkelstein JA. Thymoma and cellular immune deficiency in an adolescent. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1998;9(1):49-52.

- Duwe BV, Sterman DH, Musani AI. Tumors of the mediastinum. Chest. 2005;128(4):2893-909.

- Arend SM, Dik H, van Dissel JT. Good’s syndrome: the association of thymoma and hypogammaglobulinemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(2):323-5.

- Thompson C, Steensma D. Pure red cell aplasia associated with thymoma: clinical insights from a 50-year single institution experience. Br J Haematol. 2006;135:405–7.

- Frith J, Toller-Artis E, Tcheurekdjian H, Hostoffer R. Good syndrome and polymyositis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112(5):478.

- Raschal S, Siegel JN, Huml J, Richmond GW. Hypogammaglobulinemia and anemia 18 years after thymoma resection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100(6 Pt 1):846-8.

- Fijolek J, Wiatr E, Demkow U, Orlowsk TM. Immunological disturbances in Good’s syndrome. Clin Invest Med. 2009;32:301–6.

- Oritani K, Kincade PW, Tomiyama Y. Limitin: an interferon-like cytokine without myeloerythroid suppressive properties. J Mol Med. 2001;79(4):168-74.

- Godoy P, Campos CMC, Costa G. Associação timoma e estrongiloidíase intestinal grave. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1998;131: 481-5.

Authors

Faradiba Sarquis Serpa: Master in Clinical Immunology at Federal University of Rio de Janeiro – UFRJ. (Clinical Assistant Professor at the Superior Medical Science School of Santa Casa de Misericordia, Vitória , Espírito Santo State)

Joseane Chiabai: Master in Science by the University of São Paulo – USP. (Assistant Pediatrics’ Professor at Federal University of Espírito Santo State – UFES)

Marcos Daniel de Deus Filho: Master (Clinical Assistant Professor at Federal University of Espírito Santo State- UFES)

Firmino Braga Neto: Specialist in Pneumology. (Clinical Professor at Superior Medical Science School of Santa Casa de Misericórdia, Vitória , Espírito Santo State)