The validation of a questionnaire used to capture the perception of technical scientific knowledge on healthcare education

Abstract

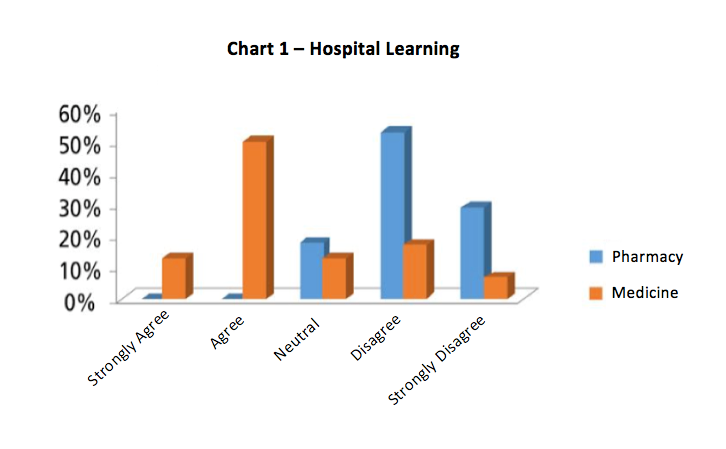

Objective: Developing and validating a questionnaire on health knowledge. Method: Descriptive, cross-sectional, quantitative design with closed questions about health education divided into five dimensions with ten indicators, thus making 50 items in Likert scale from 5.0 to 1.0. Alpha Cronbach coefficient, Pearson correlation coefficient and the statistical software SPSS 17.0 PASW Statistics version 20.0 IBM 1989, 2011were used for calculating the reliability and the internal consistency of the constructs. Result: There was statistically significant correlation (p <0.05) in the one hundred applied questionnaires. There was emphasis on the indicators of skills and general skills required for graduates’ profile: in Pharmacy, 47% of the students do not meet the profile; in Medical school, 52% did not meet the. There is 50% mismatching with articulated knowledge in the Pharmacy course and it was of 34% in the Medical School. Of the total of Pharmacy students, 82% did not meet hospital learning knowledge; among medical students, 63% fulfilled this requirement. Conclusion: The questionnaire allows viewing the teaching-learning process according to the real world and it offers reliability and reproducibility with internal consistency.

Keywords

Validation Studies; Questionnaires; Education; Health Education.

Introduction

The questionnaire concerning technical and scientific knowledge is an elaborated tool which aims to measure skills and competencies acquired in healthcare graduation courses. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) have shown concerns regarding the professional training model. Both organizations understand that such training should be guided according to the education pillars of the 21st century. Thus, students go from the mere condition of knowledge accumulators to that of individuals capable of being continuously updated by furthering on the acquired reflective thinking in order to improve their creative potential to learn how to learn, to live together, to be and to do.1

Thus, it is worth finding a way to assess whether these competencies and skills are acquired throughout academic life. Such competencies and skills demand a generalist, humanist, critical and reflective profile.2-4

Therefore, the present study aims to develop and validate a questionnaire used to analyze these skills and abilities by highlighting the desired profile, the knowledge areas as well as the learning to learn, how to live together, to be and to know how to do processes, in addition to the educational strategies used in the herein applied content. 1

The instrument uses a content model called Medical Mycology to provide the scope of the used model in other health courses.

The behavioral or cognitive educational content intensely interacts with education theories and it depends on social, political, cultural and economic factors.5 Whenever the “learn how to learn” process is contextualized, it is noticeable that teaching does not mean transferring knowledge, but creating possibilities for self -production or self-construction.6 Surveys from studies in this field reveal that knowledge construction meets learning in public policies related to social development and it seeks instruments to measure learning evidences.7,8 The social and cultural contexts can discuss the learning process in the healthcare field by applying a questionnaire whose content prioritizes the evidence that education in the community is based on real conditions which legitimize causes arising from facts.9

Healthcare education deals with particular scenarios. Therefore, students must learn how to learn in order to build their own knowledge. The educator should be their driver by stimulating the knowledge of a particular subject that, in most cases, involves illness, recovery and the social environment in which the patient lives in.10

The process usually depends on the direct link to the community and on its promotion by interpersonal communication skills developed in the academic field. These fields generate reflection techniques mediated by educators and students in the classroom. 11

When one wishes to define or investigate competencies and skills, it is important dissociating them by function, knowhow and by the ability of knowing how to be and to live. One must understand that for an individual to express its own skills, it is demanding that he/she becomes skillful. Such feature provides the evidence of being competent.12 However, competency is directly associated to grasping and understanding the bio-psycho-social situations presented by the real world. The acquisition of skills grounded in the Phenix Taxonomy defines professional qualities based on ethical, empirical, aesthetic, symbolic, synoetic and synoptic meanings.12,13

Thus, it is expected that the validation of the current questionnaire will improve the perception on the different knowledge forms. Therefore, students need to develop practical skills in order to become care providers and deal with permanent manageability, decision making and communication at community or hospital level.14-17 Thereby, distinguished pedagogical practices reinforce the construction of a reasonable competence profile. The acquisition of such competency can be analyzed through instruments used to assess learner’s perception. Such measuring is still a challenge for education in the current century.18-22

It is important to have a questionnaire template able to carry complexities regarding knowledge development based on expertise and skills and headed towards the promotion, prevention and the healing of diseases associated to the community’s reality.2-4,8,17 As it becomes clear, the lack of technical and scientific knowledge by health professionals may involve community healthcare issues that stand out mainly when academic tasks reaffirm knowhow on care giving.17,19 It is also worth involving the learning perception response to promote educators’ commitment to the teaching-learning process – which interferes in health professionals’ decision making process when they mean to improve quality of life in the community.20-22

Method

The literature review was the basis for the selection of variable. It structures the dimensions of questionnaire indicators and is a quantitative approach initially developed and designed to become a cross-sectional descriptive study.

The studied population consisted of academics attending college healthcare courses – 29 Pharmacy students and 46 from the Medical school, regularly attending the senior year, totaling 75 students. The questionnaire was applied at School of Sciences of Santa Casa de Misericordia (Emescam), in Espírito Santo State, Brazil, between 2008 and 2009. All the participants signed the Informed Consent Form (IC).

The template was divided into five dimensions containing ten indicators each, totaling 50 items measured by means of Likert scale – from 5.0 to 1.0 points – for percentage calculation and score determination. The scale scores 10 to the weakest evidence and 50 to the strongest one; scores between 50 and 40 points are considered to be the best ones. The four knowledge score dimensions are determined through values given by the number of questions and the sum of points from the options of choice (5 points: strongly agree; 4 points: agree; 3 points: neither agree nor disagree; 2 points: disagree; and 1 point: strongly disagree). The fifth dimension score uses the expressions: 5 = always; 4 = often; 3 = few times; 2 = almost never; 1 = never. The best score is considered to be the one closer to the sum of points from response number 5-4.23

Indicators in each dimension are distributed according to subjects dealing with the following contents: generalist, humanist, critical and reflexive attitude profiles; knowledge fields associated to clinical skills; competencies and general skills linked to the learning how to learn, to live and to be processes; knowhow on clinical skills; and educational strategies developed during the learning process. The dimensions cover the theoretical activities and practices in the general teaching-learning process; in rural, urban and hospital internships; and in the primary care and public health activities, according to the questionnaire model shown in table 1.

Prior to the real application, a pre-test pilot experiment was carried out with 20 students from each of the studied courses who were attending their first college years, thus totaling 40 answered instruments – these students actually did not participate in the final sample.

The calculation of the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient defines reliability and the internal consistency of the constructs’ indicators within the dimensions. Pearson’s correlation coefficient corroborates the link among indicators to measure the significant correlation among items ranging from -1 to 1. The statistical software SPSS 17.0 IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0 IBM 1989, 2011was used an it showed statistically significant correlation coefficient (p-value <0.05) .24, 25

Result

Table 1 shows the internal consistency of dimensions 1-4 in the 75 (100%) completed questionnaires.

Table 2 illustrates the correlation coefficient between competency indicators and the “know how to do” clinical skill.

Graphic 1 highlights the competency indicators and general skills needed to fulfill the desired profile. Once analyzing a dimension, one can clearly notice that the percentage is diluted by respondents’ different perception levels. Such facility to understand and interpret can be observed in other dimensions of the questionnaire.

The correlation coefficient among questions corroborates the significant relation among items, as shown in Table 3.

The dimension scores can be separately calculated according to the students’ responses, as shown in Table 4.

Discussion

It is recommended that the preparation of an education questionnaire must keep the learning content in mind. It should get individuals’ theoretical and practical participation and focus on initiatives linked to professional behaviors, collective trends, surrounding external expressions and labor.17,20 It is also worth remembering the need for involving educational activities focused on humanism in its preparation. Therefore, if teaching was just technicism, the focus would not be on the subject, but on the object.1,6

It is demanding to explore the evolution of health education processes related to epidemiological studies by using a measuring instrument. The collected data help students to understand why disease development and humanism as well as critical and reflective attitudes should be drawn from the social environment according to the observations upon patients and individuals within their social circle. The urban environment leads to factors that affect citizens. Such factors need to be taught to and perceived by students, since they have to measure their level of understanding about the disease by analyzing the factor through its social projection, in order to achieve patients’ recovery, protection and health. Complex problems faced by society can be shared with students by interdisciplinary contact and by the performance of good educational practices.10,11

Analyzing students’ perception about the development of educational skills by emphasizing health education in urban areas and the community involvement helps expanding their profile. Improved perception enhances the quality of life in the community and makes citizens more critical and reflective. Health education is based on problems experienced by students when they deal with individuals in their social context. It awakes the practical knowledge up and redefines the learning context in which omission may often lead to losses and damages to the community and to the students’ formation.5,12

Investigating students’ perception about health education, in face of community problems, helps conceptual learning activities and makes them become complete in terms of attitude and procedures. Thus students open their eyes to new observation, discovery and concept development processes, including those related to epidemiology and its interfaces. When teaching emphases the communities, more frequent diseases in this environment are evidenced and closely studied.8,19

Diversified educational problems regarding urban and rural areas are still reality in some countries. Therefore, the learning educational content needs to link facts associated to students’ knowledge on rural issues. Those who do not acquire such knowledge at the end of their graduation period may not demonstrate the necessary competencies and skills for their professional life, mainly the competencies and skills related to public policies.2-4

It is worth investigating the learning perception about diseases treated in primary care routine, since such knowledge helps students understanding several symptoms and diagnosing cases in the community, whether in the ambulatory clinics or in hospitals. If students disregard the daily life in the communities where they will work in, they may cause knowledge losses that might lead to damages to human beings.6, 16,17,19

The investigation based on the healthcare education questionnaire must highlight the value of learning what students question about primary care. Therefore, in this case, the healthcare learning process in the contemporary world goes from simplicity to complexity; and it involves integrative procedures that cover social aspects in diversified scenarios.10,15,17,21

The investigation of hospital education perception must check if the teaching-learning process is reasoned for patients’ recovery. Health education must also involve theories regarding knowledge construction, which often demands deep and accurate knowledge in order to achieve organized network activities. However, it implies a logical reasoning balance to deal with problems presented by hospitalized patients.9-11

Health education within the hospital involves procedures and specific moments when students and educators can take the advantage of enhancing opportunities to understand the subject and improve knowledge. Often, such goal is lost when educators develop their work focused on themselves. Developing health education based on a hospital-centered character has become quite necessary nowadays. However, such process should be linked to community education.8,11,13

The pillars of an innovative education help reflecting on the indicators of each questionnaire dimension and it strengthens concepts regarding interpersonal aspects of transmissivity, contagion, popular education and integrality. Healthcare education emphasizing public health has become a concern since the 19th century. Hygiene standards and their control are still a concern that deals with concept definitions based on decrees and laws, with breaking technologies that overcome historical changes based on biological conceptions and with the widely discussed biodiversity in the modernized world.21

In 2001, Delors presented a reflection about the education learning process in the 21st century. The reflection was based on performance and attitudes. Thus, the general skills and competencies developed during graduation are supported by technical-scientific knowledge. Therefore, such skills and competencies are translated into the learning to learn, to be, to live together and to do processes. Thus, the current studies aims to discuss different forms of healthcare education using innovative techniques by unfolding the educational discussions on students’ competence acquisition and by developing accumulated knowledge based on critical and reflective approachs.1-4

In fact, studies on the acquired skills and abilities can be observed, perceived and classified. They are also used to raise hypotheses, carry out deductions and generalize ideas, since they reflect students’ cognitive and behavioral aspects.7,9,14 The observation process using a questionnaire can be guided or assisted in order to lead to specific information on functions and knowledge, such as on a particular function field based on professional attitudes.16,18,22

The dimension involving educational strategies highlights the way study groups have changed due to technology. The educator needs to be aware of these changes because in the near future they will generate new paradigms, since the current ones are being broken and new communication ways are arising through electronic conversation.10,13 Currently, it is common to find students preparing their work group through information generated in the Internet. Thus, there is another type of communication group emerging nowadays. Interdisciplinarity helped the health sector at the millennium turn and it was characterized by knowledge sharing, fragmented labor actions and the expanded understanding about health related issues.5,11

Interdisciplinary exercises in universities require deep changes in the academic life. One of these changes is the opening of effective spaces for its performance during research and extension practices. In fact, exerting university education focused on the curriculum and its reformulation is not enough.15 It is necessary to experience it in order to reach an active integration among students, educators and interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary communities.7,20

In fact, the students community is going through social changes because individuals’ scientific production capacity often faces new insights within the learning framework.1,5

Test result stability and the degree of accuracy give reliability to the questionnaire construction; the more homogeneous the test is, the more reliable.23,25

Conclusion

The questionnaire completed the object of study and its interpretation can be applied to healthcare graduation courses in order to broaden the understanding of an education perception based on the everyday life in the real world; however, it involves skills and competences. Data identification makes result interpretation reliable. The application of the questionnaire clearly leads to the achievement of the herein described aim and it favors its reproduction.

References

- Delors J. Educação: um tesouro a descobrir. Relatório para a UNESCO da Comissão Internacional sobre Educação para o Século XXI, 4a ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2001.

- Brasil. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais do Curso de Graduação em Medicina. Resolução CNE/CES 4, de 7 de Novembro, 2001.

- ______ Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais do Curso de Graduação em Farmácia. Resolução CNE/CES 2, de 19 de Fevereiro, 2002.

- ______ Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais do Curso de Graduação em Medicina.Resolução CNE/CES 2, de junho, 2014.

- Peres CM, Andrade AS, Garcia SB. Atividades extracurriculares: multidisciplinaridade e diferenciação necessária ao currículo. Rev Bras Ed Med. 2007; 31 (3) :203-211.

- Freire P. Pedagogia da autonomia. Saberes necessários à prática educacional.Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 2002.

- Bradley P, Herrin J. Development and validation of an instrument to measure knowledge of evidence-based practice and searching skills. Med Educ Online. 2004; 9: 15–19.

- Venturelli J. Educación médica. Nuevos enfoques, metas y métodos. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. OPAS, OMS, Washington, D.C., 2000.

- Johnson JM, Leung GM, Fielding R, Tin KYK, Ho LM. The development and validation of a knowledge, attitude and behavior questionnaire to assess undergraduate evidence-based practice teaching and learning. Med Educ. 2003; 37(11): 992–999.PMCID: PMC3078051. NIHMSID: NIHMS257059.

- Tefaha L, Astorga C, Lobo E, Jiménez M, Czehaj M., Naigeboren GM. Enseñando a educar en salud Eje temático: La institución y los actores. Rev Congr Méd de la Fac de Med, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Argentina, 2004.

- Grosseman S, Stool S. O ensino-aprendizagem das relações médico-paciente: Um estudo de caso com estudantes do último semestre do curso de Medicina. Rev Bras Edu Med. 2008; 32 (3): 301-308.

- Holyfield LJ, Miller BH.A tool for assessing cultural competence training in dental education. J Dent Educ. 2013;77 (8): 990-7.

- Tapajós R. Objetivos educacionais na pedagogia das humanidades médicas: Taxonomias alternativas (campos de significados e competências). Rev Bras Educ Med. 2008; 32 (4): 500-506.

- Hendricson WD, Rugh JD, Hatch JP, Stark DL, Thomas Deahhl T, Wallmann ER. Validation of an Instrument to Assess Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) Knowledge, Attitudes, Access and Confidence. J Dent Educ 2011;75(2):131-144. PMCID: PMC3078051. NIHMSID: NIHMS257059.

- Itikawa FA, Afonso DH, Rodrigues RD, Guimarães M A M. Implantação de uma nova disciplina à luz das diretrizes curriculares do curso de graduação em Medicina da Universidade do estado do Rio de Janeiro. Rev Bras Edu Med. 2008;32(3):324-332.

- Grant J, Stanton F. The effectiveness of continuing professional development. Medical Education Occasional Publication. 2000. ASME Edimburhg.1-39.

- Machado MFAS, Monteiro EMLM, Queiroz DT, Vieira NFC, Barroso MGT. Integralidade, formação de saúde, educação em saúde e as propostas do SUS – uma revisão conceitual. Ciências & Saúde Coletiva. 2007; 12 (2): 335-342.

- Fritschel L, Greenhalgh T, Falck-Ytter Y, Neumayer H, Kunz R. Do short courses in evidence based medicine improve knowledge and skills? Validation of Berlin questionnaire and before and after study of courses in evidence based medicine. BMJ. 2002; 325 (7376): 1338–1341. PMCID: PMC137813.

- Bensen CP, Netto SM, Da Ros MA, Silva FW, Silva CG, Pires MF. A estratégia saúde da família como objeto de educação em saúde. Saúde e Sociedade. 2007; 16 (1): 57-68.

- Rodrigues CA, Kolling MG, Mesquita P. Educação e saúde: um binômio que merece ser resgatado. Rev Bras Educ Med. 2007; 31 (1): 60-66.

- Conversani DTN. Health education in the State of São Paulo: a reflexion based in its historical routes. Tese de Mestrado. São Paulo, Brasil, 2004.

- Raymundo VP. Construção e validação de instrumentos: desafio para psicolinguísticas. Letras de hoje. 2009; 44: 86-93.

- Hernández-Sampieri R, Baptista LP, Hernández-Collado C. Metodologia de la investigación. 4ª ed. México, DF: Mcgraw-Hill Interamericana, 2006.

- Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham, RL, Black W. Multivariate data analysis. 5a ed. New York: Prentice Hall, 1998.

- Cronbach LJ, Meehl PE. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 1955.

Attachments

Table 1 – internal consistency of Dimensions

| DIMENSIONS | ALPHA |

| 1 | 0,806 |

| 2 | 0,865 |

| 3 | 0,908 |

| 4 | 0,800 |

Table 2 – Correlation Coefficients

| INDICATORS | CORRELATION COEFFICIENTS |

| Laboratory Diagnostics | 0,504* |

| Clinical diagnosis | 0,757* |

| Clinical treatment | 0,719* |

| Prevention | 0,599* |

* Correlation coefficients statistically significant (p-value <0.05).

Table 3 – Correlation coefficients between the topics of Dimension 5

| TOPICS | CORRELATION COEFFICIENTS |

| Real problems | 0,557* |

| Combining simulation with real cases | 0,715* |

| Clinical cases | 0,641* |

| Community education | 0,650* |

| Scientific evidence | 0,620* |

| Interdisciplinary | 0,650* |

| Group activity | 0,709* |

| Multidisciplinary education | 0,605* |

| Internet | 0,657* |

| Student recovery | 0,670* |

* Correlation coefficients statistically significant (p-value <0.05).

Table 4 – Pharmacy and Medicine Student survey results

| DIMENSIONS | MEAN ± STANDARD DEVIATION | RESULTS

VARIATION |

P-VALUE | |

| PHARMACY | MEDICINE | |||

| 1 | 19,03 ± 5,39 | 22,76 ± 4,83 | 10-50 | 0,003* |

| 2 | 6,07 ± 2,72 | 12,60 ± 3,77 | 10-50 | 0,000* |

| 3 | 29,23 ± 8,27 | 36,24 ± 6,99 | 10-50 | 0,000* |

| 4 | 47,83 ± 14,04 | 50,18 ± 12,5 | 10-50 | 0,451 |

| 5 | 14,43 ± 4,53 | 15,40 ± 5,51 | 10-50 | 0,712 |

* p <0.050, rejects the hypothesis of equality.

Table 5: Questionnaire on the Perception of Knowledge Acquisition in health courses

| COURSE:………………. TERM: …………. STUDENT AGE:……………….SEX: M…. F…..

INSTITUTE:……………………………………………………………………………………….DATE: …/…/…………… MARK WITH AN X THE ALTERNATIVE THAT INDICATES YOUR PERCEPTION REGARDING THE ACQUISITION OF TECHNICAL-SCIENTIFIC KNOWLEDGE IN THE SUBJECT / CONTENTS:……………………. 5= strongly agree; 4= agree; 3= neutral; 2= disagree; 1= strongly disagree. |

||||||

| Nº | DIMENSION 1: WANTED GRADUATE PROFILE | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 01 | General learning | |||||

| 02 | Theoretical knowledge | |||||

| 03 | Practical knowledge | |||||

| 04 | Articulated knowledge with urban communities | |||||

| 05 | Articulated knowledge with rural communities | |||||

| 06 | Basic care procedures | |||||

| 07 | Hospital learning | |||||

| 08 | Public Health Procedures | |||||

| 09 | Critical and reflective training | |||||

| 10 | Humanistic education | |||||

| Nº | DIMENSION 2: KNOWLEDGE AREAS OF TRAINING | |||||

| 11 | Health care | |||||

| 12 | Health problems research | |||||

| 13 | Health problems evaluation | |||||

| 14 | Interventions development | |||||

| 15 | Hypothesizing | |||||

| 16 | Ethics training | |||||

| 17 | Project development training | |||||

| 18 | Ability to identify signs and symptoms | |||||

| 19 | Care and procedures Innovation | |||||

| 20 | Development of public policies for health | |||||

| Nº | DIMENSION 3: LEARNING SKILLS TO LEARN, BE AND LIVING | |||||

| 21 | communication | |||||

| 22 | interpersonal relationships | |||||

| 23 | Development of autonomy | |||||

| 24 | Authorship Development | |||||

| 25 | Lifelong learning | |||||

| 26 | Team work | |||||

| 27 | public administration | |||||

| 28 | Education in foreign languages | |||||

| 29 | Learning Ability to learn | |||||

| 30 | Ability to know how to live | |||||

| Nº | DIMENSION 3: KNOWHOW SKILLS | |||||

| 31 | Laboratory diagnostics | |||||

| 32 | Clinical diagnosis | |||||

| 33 | Clinical treatment of diseases | |||||

| 34 | Health protection | |||||

| 35 | Health promotion | |||||

| 36 | Health recovery | |||||

| 37 | Bio psychosocial problems of illness | |||||

| 38 | Hospital training | |||||

| 39 | Training/ rural stage | |||||

| 40 | Training public health | |||||

| MARK WITH AN X THE BEST OPTION ACCORDING TO THE STRATEGIES USED IN THIS CONTENT / DISCIPLINE

5= always; 4= often, 3= sometimes, 2= rarely, 1= never |

||||||

| Nº | DIMENSION 5: EDUCATIONAL STRATEGIES OF LEARNING | |||||

| 41 | Real problems | |||||

| 42 | Clinical cases | |||||

| 43 | Group activity | |||||

| 44 | Interdisciplinary | |||||

| 45 | Scientific evidence | |||||

| 46 | Multidisciplinary education | |||||

| 47 | Community education | |||||

| 48 | Simulations with real cases | |||||

| 49 | Internet | |||||

| 50 | Student recovery | |||||

Authors

Maria das Graças Silva Mattede: Doctor. School of Science of Santa Casa de Misericordia, Vitória, Espírito Santo State (Professor)

Diosnel Centurión: Doctor, PhD. Universidad Autónoma de Asunción (UAA) (Professor)